Far from being an epicenter of ‘cleantech,’ the Bay Area actually is host to some of the largest oil corporations exploiting Canada’s oil sands.

Sidney Martin Blair, Bechtel’s man in Canada, an early proponent of mining the oil sands of Alberta.

In 1951 Sidney Martin Blair, the vice president of Bechtel Canada, visited Alberta at the behest of the regional government to examine the economic case for mining the thick deposits of bitumen resting underneath much of the boreal forests and grasslands that reach up and around frigid Lake Athabasca. Blair was no stranger to what are known popularly today as the tar, or oil sands. In 1924 Blair, who grew up in the northern clime of Canada’s interior, submitted his thesis for a Master of Science degree from the University of Alberta: “An Investigation of the Bitumen Constituent of the Bituminous Sands of Northern Alberta.” His later study of the oil sands for Alberta came to be known as the Blair Report and served as the founding document for what is becoming one of the largest industrial projects in human history, and one of the most dire environmental threats we have ever faced.

On the economic end Blair concluded, importantly, that extraction of a barrel of oil from the Alberta sands had reached a cost of $3.10, while that same barrel would be worth $3.50 in the regional and Western U.S. markets. It was still high above the cost of pumping sweet crude from plentiful wells in Canada and south of the border in America’s abundant oil plays of Colorado, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming, but the price arrangements were headed toward more parity over the long-term, Blair and others surmised. Easy to drill gushers would disappear by the 1980s in the United States, leading to increasing imports of more expensive oil, and finally to the fracking boom which requires much higher levels of capital and investment to squeeze petroleum from fickle rock formations. The economic price per barrel of oil from Alberta’s bituminous sands would only become more attractive.

Blair’s affiliation with Bechtel was no accident. The secretive corporation was by the 1940s a major player in the petroleum industry, building pipelines and other infrastructure for oil giants, and national oil corporations all over the world. Bechtel’s close ties to the U.S. military and CIA gave the company access to the highest levels of government in the Middle East, South America, Europe, and Asia, where newly rich princes and anti-communist dictators flush with cash, and with U.S. foreign aid, sought to build gargantuan energy projects. The Bechtels and their close associates made billions many times over.

Where once existed a Boreal forest, now an open pit oil sands mine worked by shovels and trucks.

The Bechtel family viewed Canada’s oil sands as a potential source of profits many years before the regional government and oil corporations were willing to invest. Blair gave Bechtel entry when the time came; in 1962 Bechtel began construction of the Athabasca Tar Sands project in Alberta’s northern reaches for the Greater Canadian Oil Sands company. It was the first large scale attempt to mine and refine the bitumen into oil and other hydrocarbon products. Imitators, from smaller independent companies to the big majors like Exxon and Chevron, would eventually pile aboard.

Over the next several decades Bechtel built many of the “upgrading facilities” as the giant cookers that heat and separate the filthy mixture of bitumen, sand, and water, are called. Today Bechtel, along with its subsidiary Bantrel, remains one of the largest oil sands engineering firms in the world. Bantrel designs and Bechtel builds. Over the last two decades Bantrel designed and Bechtel built several massive upgraders for Suncor, the corporate successor of the Greater Canadian Oil Sands company.

Suncor’s open pit mines lie northwest of Fort McMurray. Miles of scraped-bare earth crawl with one-hundred ton shovel excavators and trucks capable of hauling four-hundred tons of earth across miles of devastated moonscape to waiting crushers and conveyors. The tar sands mines are visible from space, probably even from the moon.

Suncor’s open pit mines lie northwest of Fort McMurray. Miles of scraped-bare earth crawl with one-hundred ton shovel excavators and trucks capable of hauling four-hundred tons of earth across miles of devastated moonscape to waiting crushers and conveyors. The tar sands mines are visible from space, probably even from the moon.

Suncor’s bitumen is processed on site resulting in the equivalent of over 300,000 barrels of oil equivalent extracted each day. In-situ extraction, a process of pumping oil from deeper sand deposits after its is heated and precipitated into thick veins within the soil using steam and other injectants, provides another 100,000 barrels, much of which is piped to a refinery in Denver.

Suncor aspires to produce a million barrels of oil a day from its tar sands holdings. Bechtel will likely build the facilities.

Bechtel today actually plays second string to another San Francisco corporation when it comes to providing engineering and construction services to exploit the oil sands. Last year URS, the giant engineering company that Dianne Feinstein’s husband Richard Blum once owned a big stake in, bought out Flint Energy Services, a Canadian oil and gas production services provider, for $1.25 billion. Flint is less well-known that other oil services companies like Schlumberger and Halliburton, but it does the same work.

In-situ oil sands mining utilizes steam and other heated injectants to emulsify bitumen deep in the ground. It is then pumped to the surface and piped to nearby separation and treatment plants. As much as 80 percent of Canada’s tar sands is too deep to pit mine, meaning that in-situ extraction is of paramount importance to the fossil fuel industry’s plans.

One of URS’s biggest and newest oil sands contracts is a $130 million project to lay 43 miles of pipes that will shoot steam deep underneath the surface of the Wood Buffalo region, a remote and mostly forested plain northeast of Fort McMurray. This single in-situ tar sands project will extract 85,000 barrels of bitumen a day according to the application filed by Canadian Natural Resources, Inc. URS is carrying out several similar projects to heat up enormous expanses of the Canadian landscape far beneath the surface in order to liquify and suck out bitumen.

The in-situ tar sands extraction method is less destructive to the immediate landscape than open pit mining, but it poses the greater risk in terms of climate change. Approximately 80 percent of the oil sands are buried too deep to excavate. Thus in-situ extraction methods being engineered by URS and Bechtel are being used to tap these hundreds of billions of barrels equivalent of oil. Needless to say, if this happens levels of CO2 in the atmosphere will surpass the counts that most scientists say will lead to catastrophic rises in global temperatures.

The roads, pipelines, and “pads” —the patches of cleared earth upon which drilling rigs operate and where valves and other machinery are built— required for in-situ oil sands mining are also visible from satellite photos of the region. From high above the roads and pads of the region’s in-situ oil plays look like tan nets cast over the landscape, covering hundreds of square miles, cutting wild boreal forests into neat, logical grids.

Expansion of the open pits and in-situ fields of the tar sands will all happen regardless of whether the Keystone XL pipeline is approved, but URS noted in their annual report for the last year that such a decision would impact their earnings as it would significantly restrict expansion. “Should the proposed Keystone XL pipeline project application be denied or delayed by the federal government,” explained the company, “then there may be a slowing of spending in the development of the Canadian oil sands.”

Martin Koffel, CEO of URS Corp. URS is also one of the largest U.S. military contractors, and co-operates the multiple sites within the U.S. nuclear weapons complex, including the nation’s two primary weapons design and testing labs.

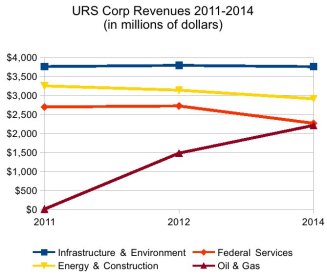

Regardless, San Francisco’s URS is going all in for the tar sands. On a recent conference call URS’s long-time CEO Martin Koffel said, “Flint, in our view, is the perfect fit for us, given our long-held ambition to expand our position in the oil and gas market.” Koffel noted that 20 percent of URS Corp’s revenues are now dependent upon oil and gas projects, and most of these will involve the Canadian oil sands, or fracking projects in the United States. “We’re more than enthusiastic about this sector,” said Koffel.

Other Bay Area corporate giants have been eager to invest in the tar sands in recent years. San Ramon-headquartered Chevron owns interests in the Athabasca Oil Sands Project near Fort McMurray, an operation that pipes out over a quarter million barrels each day. Chevron has been one of the most aggressive oil and gas corporations in the political sphere. The company has contributed millions in recent years to campaigns aimed at gutting state and federal environmental laws. Chevron’s army of lobbyists are active on Capitol Hill and across various oil and gas-rich states pressing to keep lucrative subsidies in place, and to prevent climate change and other environmental bills from being considered. Chevron is also one of the sponsors of MIT’s Energy Initiative, the pro-oil, gas, and coal think tank from which Obama’s current Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz hails.

Fluor Corporation, an engineering rival of URS, has an office in the East Bay city of Dublin that employs approximately one hundred engineers. When it opened its Dublin office in 2008, Fluor cited its proximity to Chevron’s East Bay operations and headquarters as a deciding factor for the move.

Fluor’s global headquarters is in Irving, Texas, just one mile down the road from another of the company’s key clients, the world’s largest oil corporation, ExxonMobil. Fluor’s East Bay office employes about one hundred engineers who plug away full-time on oil and gas projects. For Chevron Fluor is designing and building facilities at the Muskeg River Mine, a giant oil sands site 75 miles northwest of Fort McMurray that will spit out 155,000 barrels of bitumen each day for three decades. This will result in a total of 1.6 billion barrels of bitumen that will be refined into upwards of billion barrels equivalent of oil.

That the San Francisco Bay Area is now an epicenter of oil sands engineering and services is ironic given the region’s reputation for environmentalism, and strong pushes for renewable energy development by various local governments. San Francisco, Sonoma County, Marin County, and Richmond are all developing community choice aggregation programs to replace PG&E as their utility, and to develop local renewable sources of electricity. San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors voted just last month to urge the city’s pension system to divest about half a billion dollars from stocks in oil, gas, and coal companies, some of them the same corporations named above. Berkeley’s mayor is urging similarly, and is even pressing California’s massive public employees pension system CalPERS to divest its stock and bond portfolios from fossil fuel energy companies.

The Bay Area’s business community plays up its green credentials, even if it’s undeserved. Every company touts “sustainability” as a major goal. Even URS and Bechtel both publish glossy annual sustainability reports touting beach clean ups, community garden volunteer days, light bulb replacements in their offices, and the number of their employees who bike or take the train to work.

If they succeed in their quest to exploit Canada’s mostly un-tapped oil sands, in the not-too distant future URS and Bechtel employees might be cleaning up beaches that have shifted miles inland from calamitous rises in sea level, and they might be biking to work in 120 degree heat.

According to James Hansen, the recently retired chief climate scientist of NASA, the oil sands are an end game for the environment.

“Canada’s tar sands, deposits of sand saturated with bitumen, contain twice the amount of carbon dioxide emitted by global oil use in our entire history,” wrote Hansen in a New York Times op-ed last year.

“If we were to fully exploit this new oil source, and continue to burn our conventional oil, gas and coal supplies, concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere eventually would reach levels higher than in the Pliocene era, more than 2.5 million years ago, when sea level was at least 50 feet higher than it is now. That level of heat-trapping gases would assure that the disintegration of the ice sheets would accelerate out of control. Sea levels would rise and destroy coastal cities. Global temperatures would become intolerable. Twenty to 50 percent of the planet’s species would be driven to extinction. Civilization would be at risk.”

Suncor’s

Suncor’s