Bay Area Council CEO Jim Wunderman, BART director Grace Crunican, and MTC representative Tom Bulger in the Capitol with Rep. Nancy Pelosi in 2011.

On October 3 a business lobbying organization released a poll claiming that Bay Area residents are in “overwhelming agreement” that BART workers should accept the current contract proposal offered by the transit system’s management in order to avoid another strike. That offer would actually amount to a pay cut for most BART employees, but it was described in the poll as a “raise of 10 percent.” The survey’s overall design seems geared to elicit a result favoring BART management. No doubt this is because the business lobby that paid for and helped engineer the poll has an interest in driving down labor costs and freeing up BART’s revenue for system expansion.

The lobbying group that paid for the poll is the Bay Area Council, or BAC. The BAC was formed in 1944 as a coordinating committee of the region’s biggest banks, construction companies, manufacturers, oil giants, and real estate corporations, most of them headquartered in downtown San Francisco. The impetus to create the BAC stemmed from the frustrations of elite corporate executives who, during World War II, worried that the Bay Area’s fragmented geography and multitude of county and city governments would prevent the creation of grand transit and industrial projects. The war time boom minted huge fortunes for these tycoons, but they feared northern California’s auto-driven sprawl would diminish real estate values in their cherished urban core, San Francisco, and further that it would drive up operating costs for their companies as their white collar employees, and some of their peer companies, dispersed to the suburbs.

“These prospects were greeted with exaggerated gloom in San Francisco,” wrote Melvin Webber in a 1976 study of BART. Webber was the founder of Berkeley’s Transportation Center, and an influential author of an early analysis of BART’s impact on the region. Webber found the origins of BART in both the financial and political interest of San Francisco’s wealthy elite:

“Surely, no other American city is as proud and narcissistic-no civic leaders elsewhere so obsessed by their sense of responsibility for protecting and nurturing their priceless charge. The idea that San Francisco might go the way of Newark or St. Louis was utterly abhorrent. And so it was, as the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce proudly reported in a multi-page advertisement in Fortune, that the civic leaders of San Francisco and their neighboring kin initiated a major effort to keep the Bay Area from going the way that cities of lesser breed were headed. The campaign was masterful in both conception and execution.”

Alan Browne, a senior vice president at Bank of America who participated in this masterful campaign to establish BART said the problem was, “essentially just a breakdown on the movement of people,” from the hinterlands to the urban core.

Joining Browne was Adrian Falk, the president of S&W Foods. Falk helped raise funds and coordinate the 1962 ballot campaign to launch BART. S&W Foods, today known as Del Monte, the $3.8 billion corporate agribusiness giant, is still headquartered three blocks from BART’s Embarcadero Station. After helping wage the successful public relations campaign for BART’s creation, S&W’s Falk became the first president of BART’s board of directors.

Falk told the local newspapers quite frankly that the main purpose of BART was to create the necessary people moving infrastructure to benefit the wealthy downtown corporations already located in San Francisco. “Certain financial, banking, and industrial companies want to be centralized, want to have everyone near each other,” said Falk. “They don’t want to have to go one day to Oakland, the next day to San Jose, the next day to San Francisco.” (For a lengthy discussion of BART see John Dickey’s Metropolitan Transportation Planning, 2nd Edition, 1983, p. 378).

BART’s first general manager was a former executive with the Western States Oil and Gas Association, John Pierce. The oil industry’s dominant West Coast driller and refiner, Standard Oil of California, was at the time headquartered two blocks from BART’s planned Montgomery Street Station. Support from oil companies was just one sign that BART was never meant to reduce freeway traffic and reliance on oil. The Bay Area’s freeways were still planned to expand in size by multiples. (Years later Standard of California, broken off the larger oil monopoly and renamed Chevron, moved to San Ramon, far off the BART line.)

Executives of Bank of America, Wells Fargo, and Crocker National Bank, all with their headquarters just blocks from BART’s planned stations running along Market Street, were instrumental in the campaign to create the transit system. For example, Bank of America CEO Carl Wente was the chair of the BAC’s rapid transit committee and chairman of the fundraising effort for the ballot measure that funded BART.

More than a few of the BAC’s corporate members made fortunes off the construction of BART.

No sooner had BART collected its first pot of sales tax revenue in 1958 then the District’s leadership paid Bechtel and Tutor to design the railway. Bechtel’s offices were again both located just blocks from where the planned funnel of BART trains would dump workers along Market Street. Bechtel, the giant engineering and construction company then busy building petroleum and nuclear plants around the world, later landed the contract to build BART’s tunnels and tubes. More recently Tutor was paid over $600 million by BART to build the SFO extension, and millions more to build the South San Francisco and San Bruno stations. The S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation to this day funds the Bay Area Council.

Bay Area banks underwrote the bonds for BART, skimming millions off the discount fees and interest payments secured ultimately by regressive bridge tolls and sales taxes.

Again, Bank of America’s Alan Browne provides a candid description of how BART’s lucrative financial and construction contracts were divvied up between San Francisco’s business lobby. “As it worked out,” said Brown in a 1988 interview, “Bechtel saw a chance to do the engineering work, and Kaiser was also involved in the idea of selling concrete and steel and engineering. PG&E could sell power; Chevron, if they took cars off the freeways, they’d be replaced with other cars. So that was another factor, and they all could see that they were going to benefit.”

As for Bank of America, Browne understated the benefit the San Francisco financial behemoth reaped from BART’s construction and operations:

“We were pretty good at investing. We weren’t as successful in bidding for the securities [BART bonds], and I used to be amused because all of our competitors in the banking world had no part at all in the growth and development of the BART concept. But when the bonds were finally approved and were being offered for sale, they were in there with both feet. So they were trying to prove something. All that we were able to obtain out of the spoils of victory were being made the trustee and fiscal paying agent. Which was not a big item, but it was one thing.”

That one thing was profitable enough for Bank of America. Other financial institutions made millions over the years financing BART, and Wells Fargo and Crocker National (merged into Wells Fargo in 1986) saw their downtown San Francisco fortunes boom.

The foundations established by these banks currently funnel dollars to support the Bay Area Council’s activities, including the recent poll it paid for about BART. Bank of America Foundation, US Bank, and the Wells Fargo Foundation all channel money to BAC.

Is it any surprise then that the Bay Area Council, a big business lobbying group, with its origins in the campaign to create BART and finance it with regressive sales taxes and passenger fares, would sponsor a poll today pressuring BART’s workers to accept pay cuts?

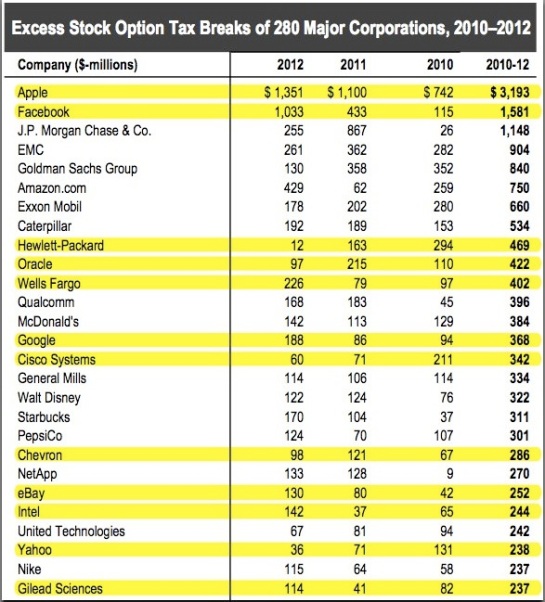

More than a few of the current members of the Bay Area Council have a strong financial interests in cutting the compensation of BART employees in order to free up more revenue for costly system expansions.

The Orrick Herrington & Suffcliffe law firm was paid a pretty penny in 2010 bond as counsel to BART on a $129 million sales tax bond flotation. Orrick law is a member of the BAC. Last year Orrick earned another pot of money on BART’s $240 million sales tax bonds. BART is a big client for Orrick. Every time the transit district needs to borrow money it’s likely that Orrick will be paid to help structure a deal.

The trustee on most of BART’s bonds is US Bank, a member of the BAC, which basically inherited the business from Bank of America.

In 2009 BART’s board of directors fed at least two $15 million dollar contracts to URS Corporation, another member of the BAC, for various engineering and construction work related to the system’s expansion. In 2007 URS won a $10 million contract from BART to manage construction upgrades of BART’s elevated train lines. URS makes a lot of money from BART’s capital budget, having helped build three BART stations. A vice president of “corporate strategic planning” with URS currently sits on the Bay Area Council’s board of directors.

The real estate developer TMG Partners has multiple projects that will be affected by BART’s investments of public funds. Just earlier this year the San Francisco Business Times straightforwardly published an article about TMG entitled, “Landlords snap up sites near BART, Muni stops.” On its web site TMG says its vision is to “take advantage of [an] under-construction BART station,” by building an 1,100 unit apartment complex with a hotel in San Bruno where real estate values are poised to climb thanks to BART. TMG’s chairman and CEO Michael Covarrubias is a board member of the Bay Area Council, and his company is a corporate member.

Another member of the BAC, the engineering company CH2M Hill, was awarded a $25 million contract earlier this year to advise BART on vehicle maintenance and refurbishment. CH2M Hill’s prime contract includes multiple subcontractors like BAC members URS and Arup North America.

The Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman law firm is another Bay Area Council member with deep financial links to BART. Pillsbury has been paid millions by BART to lobby for the transit agency in Sacramento for many years. A Pillsbury partner Robert James has represented BART in real estate deals around planned stations. Robert James is a board member of the BAC.

Bay Area Council member Citibank has underwritten multiple BART bonds in prior years. Citibank has also sold BART complex financial derivatives like the 2004 interest rate cap that cost BART $245,000. Citibank’s Rebecca Macieira-Kaufmann is a BAC board member.

And of course joining all these CEOs whose companies do multi-million dollar business with BART on the board of the Bay Area Council is BART’s general manager Grace Crunican.