“No one knows who will live in this cage in the future, or whether at the end of this tremendous development, entirely new prophets will arise, or there will be a great rebirth of old ideas and ideals, or, if neither, mechanized petrification, embellished with a sort of convulsive self-importance. For of the fast stage of this cultural development, it might well be truly said: ‘Specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.'”

“No one knows who will live in this cage in the future, or whether at the end of this tremendous development, entirely new prophets will arise, or there will be a great rebirth of old ideas and ideals, or, if neither, mechanized petrification, embellished with a sort of convulsive self-importance. For of the fast stage of this cultural development, it might well be truly said: ‘Specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart; this nullity imagines that it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.'”

—Max Weber, 1905

On November 12 Facebook, Inc. filed its 178th patent application for a consumer profiling technique the company calls “inferring household income for users of a social networking system.”

“The amount of information gathered from users,” explain Facebook programmers Justin Voskuhl and Ramesh Vyaghrapuri in their patent application, “is staggering — information describing recent moves to a new city, graduations, births, engagements, marriages, and the like.” Facebook and other so-called tech companies have been warehousing all of this information since their respective inceptions. In Facebook’s case, its data vault includes information posted as early as 2004, when the site first went live. Now in a single month the amount of information forever recorded by Facebook —dinner plans, vacation destinations, emotional states, sexual activity, political views, etc.— far surpasses what was recorded during the company’s first several years of operation. And while no one outside of the company knows for certain, it is believed that Facebook has amassed one of the widest and deepest databases in history. Facebook has over 1,189,000,000 “monthly active users” around the world as of October 2013, providing considerable width of data. And Facebook has stored away trillions and trillions of missives and images, and logged other data about the lives of this billion plus statistical sample of humanity. Adjusting for bogus or duplicate accounts it all adds up to about 1/7th of humanity from which some kind of data has been recorded.

According to Facebook’s programmers like Voskuhl and Vyaghrapuri, of all the clever uses they have already applied this pile of data toward, Facebook has so far “lacked tools to synthesize this information about users for targeting advertisements based on their perceived income.” Now they have such a tool thanks to the retention and analysis of variable the company’s positivist specialists believe are correlated with income levels.

They’ll have many more tools within the next year to run similar predictions. Indeed, Facebook, Google, Yahoo, Twitter, and the hundreds of smaller tech lesser-known tech firms that now control the main portals of social, economic, and political life on the web (which is now to say everywhere as all economic and much social activity is made cyber) are only getting started. The Big Data analytics revolutions has barely begun, and these firms are just beginning to tinker with rational-instrumental methods of predicting and manipulating human behavior.

There are few, if any, government regulations restricting their imaginations at this point. Indeed, the U.S. President himself is a true believer in Big Data; the brain of Obama’s election team was a now famous “cave” filled with young Ivy League men (and a few women) sucking up electioneering information and crunching demographic and consumer data to target individual voters with appeals timed to maximize the probability of a vote for the new Big Blue, not IBM, but the Democratic Party’s candidate of “Hope” and “Change.” The halls of power are enraptured by the potential of rational-instrumental methods paired with unprecedented access to data that describes the social lives of hundreds of millions.

Facebook’s intellectual property portfolio reads like cliff notes summarizing the aspirations of all corporations in capitalist modernity; to optimize efficiency in order to maximize profits and reduce or externalize risk. Unlike most other corporations, and unlike previous phases in the development of rational bureaucracies, Facebook and its tech peers have accumulated never before seen quantities of information about individuals and groups. Recent breakthroughs in networked computing make analysis of these gigantic data sets fast and cheap. Facebook’s patent holdings are just a taste of what’s arriving here and now.

The way you type, the rate, common mistakes, intervals between certain characters, is all unique, like your fingerprint, and there are already cyber robots that can identify you as you peck away at keys. Facebook has even patented methods of individual identification with obviously cybernetic overtones, where the machine becomes an appendage of the person. U.S. Patents 8,306,256, 8,472,662, and 8,503,718, all filed within the last year, allow Facebook’s web robots to identify a user based on the unique pixelation and other characteristics of their smartphone’s camera. Identification of the subject is the first step toward building a useful data set to file among the billion or so other user logs. Then comes analysis, then prediction, then efforts to influence a parting of money.

Many Facebook patents pertain to advertising techniques that are designed and targeted, and continuously redesigned with ever-finer calibrations by robot programs, to be absorbed by the gazes of individuals as they scroll and swipe across their Facebook feeds, or on third party web sites.

Speaking of feeds, U.S. Patent 8,352,859, Facebook’s system for “Dynamically providing a feed of stories about a user of a social networking system” is used by the company to organize the constantly updated posts and activities inputted by a user’s “friends.” Of course embedded in this system are means of inserting advertisements. According to Facebook’s programmers, a user’s feeds are frequently injected with “a depiction of a product, a depiction of a logo, a display of a trademark, an inducement to buy a product, an inducement to buy a service, an inducement to invest, an offer for sale, a product description, trade promotion, a survey, a political message, an opinion, a public service announcement, news, a religious message, educational information, a coupon, entertainment, a file of data, an article, a book, a picture, travel information, and the like.” That’s a long list for sure, but what gets injected is more often than not whatever will boost revenues for Facebook.

The advantage here, according to Facebook, is that “rather than having to initiate calls or emails to learn news of another user, a user of a social networking website may passively receive alerts to new postings by other users.” The web robot knows best. Sit back and relax and let sociality wash over you, passively. This is merely one of Facebook’s many “systems for tailoring connections between various users” so that these connections ripple with ads uncannily resonant with desires and needs revealed in the quietly observed flow of e-mails, texts, images, and clicks captured forever in dark inaccessible servers of Facebook, Google and the like. These communications services are free in order to control the freedom of data that might otherwise crash about randomly, generating few opportunities for sales.

Where this fails Facebook ratchets up the probability of influencing the user to behave as a predictable consumer. “Targeted advertisements often fail to earn a user’s trust in the advertised product,” explain Facebook’s programmers in U.S. Patent 8,527,344, filed in September of this year. “For example, the user may be skeptical of the claims made by the advertisement. Thus, targeted advertisements may not be very effective in selling an advertised product.” Facebook’s computer programmers who now profess mastery over sociological forces add that even celebrity endorsements are viewed with skepticism by the savvy citizen of the modulated Internet. They’re probably right.

Facebook’s solution is to mobilize its users as trusted advertisers in their own right. “Unlike advertisements, most users seek and read content generated by their friends within the social networking system; thus,” concludes Facebook’s mathematicians of human inducement, “advertisements generated by a friend of the user are more likely to catch the attention of the user, increasing the effectiveness of the advertisement.” That Facebook’s current So-And-So-likes-BrandX ads are often so clumsy and ineffective does not negate the qualitative shift in this model of advertising and the possibilities of un-freedom it evokes.

Forget iPhones and applications, the tech industry’s core consumer product is now advertising. Their essential practice is mass surveillance conducted in real time through continuous and multiple sensors that pass, for most people, entirely unnoticed. The autonomy and unpredictability of the individual —in Facebook’s language the individual is the “user”— is their fundamental business problem. Reducing autonomy via surveillance and predictive algorithms that can placate existing desires, and even stimulate and mold new desires is the tech industry’s reason for being. Selling their capacious surveillance and consumer stimulus capabilities to the highest bidder is the ultimate end.

Sounds too dystopian? Perhaps, and this is by no means the world we live in, not yet. It is, however, a tendency rooted in the tech economy. The advent of mobile, hand-held, wirelessly networked computers, called “smartphones,” is still so new that the technology, and its services feel like a parallel universe, a new layer of existence added upon our existing social relationships, business activities, and political affiliations. In many ways it feels liberating and often playful. Our devices can map geographic routes, identify places and things, provide information about almost anything in real time, respond to our voices, and replace our wallets. Who hasn’t consulted “Dr. Google” to answer a pressing question? Everyone and everything is seemingly within reach and there is a kind of freedom to this utility.

Most of Facebook’s “users” have only been registered on the web site since 2010, and so the quintessential social network feels new and fun, and although perhaps fraught with some privacy concerns, it does not altogether fell like a threat to the autonomy of the individual. To say it is, is a cliche sci-fi nightmare narrative of tech-bureaucracy, and we all tell one another that the reality is more complex.

Privacy continues, however, too be too narrowly conceptualized as a liberal right against incursions of government, and while the tech companies have certainly been involved in a good deal of old-fashioned mass surveillance for the sake of our federal Big Brother, there’s another means of dissolving privacy that is more fundamental to the goals of the tech companies and more threatening to social creativity and political freedom.

Georgetown University law professor Julie Cohen notes that pervasive surveillance is inimical to the spaces of privacy that are required for liberal democracy, but she adds importantly, that the surveillance and advertising strategies of the tech industry goes further.

“A society that permits the unchecked ascendancy of surveillance infrastructures, which dampen and modulate behavioral variability, cannot hope to maintain a vibrant tradition of cultural and technical innovation,” writes Cohen in a forthcoming Harvard Law Review article.

“Modulation” is Cohen’s term for the tech industry’s practice of using algorithms and other logical machine operations to mine an individual’s data so as to continuously personalize information streams. Facebook’s patents are largely techniques of modulation, as are Google’s and the rest of the industry leaders. Facebook conducts meticulous surveillance on users, collects their data, tracks their movements on the web, and feeds the individual specific content that is determined to best resonate with their desires, behaviors, and predicted future movements. The point is to perfect the form and fuction of the rational-instrumental bureaucracy as defined by Max Weber: to constantly ratchet up efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control. If they succeed in their own terms, the tech companies stand to create a feedback loop made perfectly to fit each an every one of us, an increasingly closed systems of personal development in which the great algorithms in the cloud endlessly tailor the psychological and social inputs of humans who lose the gift of randomness and irrationality.

“It is modulation, not privacy, that poses the greater threat to innovative practice,” explains Cohen. “Regimes of pervasively distributed surveillance and modulation seek to mold individual preferences and behavior in ways that reduce the serendipity and the freedom to tinker on which innovation thrives.” Cohen has pointed out the obvious irony here, not that it’s easy to miss; the tech industry is uncritically labeled America’s hothouse of innovation, but it may in fact be killing innovation by disenchanting the world and locking inspiration in an cage.

If there were limits to the reach of the tech industry’s surveillance and stimuli strategies it would indeed be less worrisome. Only parts of our lives would be subject to this modulation, and it could therefore benefit us. But the industry aspires to totalitarian visions in which universal data sets are constantly mobilized to transform an individual’s interface with society, family, the economy, and other institutions. The tech industry’s luminaries are clear in their desire to observe and log everything, and use every “data point” to establish optimum efficiency in life as the pursuit of consumer happiness. Consumer happiness is, in turn, a step toward the rational pursuit of maximum corporate profit. We are told that the “Internet of things” is arriving, that soon every object will have embedded within it a computer that is networked to the sublime cloud, and that the physical environment will be made “smart” through the same strategy of modulation so that we might be made free not just in cyberspace, but also in the meatspace.

Whereas the Internet of the late 1990s matured as an archipelago of innumerable disjointed and disconnected web sites and databases, today’s Internet is gripped by a handful of giant companies that observe much of the traffic and communications, and which deliver much of the information from an Android phone or laptop computer, to distant servers, and back. The future Internet being built by the tech giants —putting aside the Internet of things for the moment— is already well into its beta testing phase. It’s a seamlessly integrated quilt of web sites and apps that all absorb “user” data, everything from clicks and keywords to biometric voice identification and geolocation.

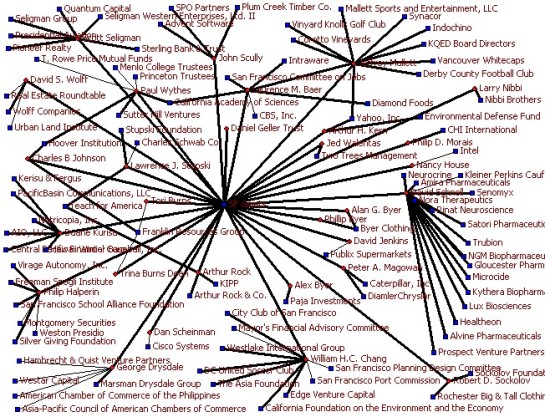

United States Patent 8,572,174, another of Facebook’s recent inventions, allows the company to personalize a web page outside of Facebook’s own system with content from Facebook’s databases. Facebook is selling what the company calls its “rich set of social information” to third party web sites in order to “provide personalized content for their users based on social information about those users that is maintained by, or otherwise accessible to, the social networking system.” Facebook’s users generated this rich social information, worth many billions of dollars as recent quarterly earnings of the company attest.

In this way the entire Internet becomes Facebook. The totalitarian ambition here is obvious, and it can be read in the securities filings, patent applications, and other non-sanitized business documents crafted by the tech industry for the financial analysts who supply the capital for further so-called innovation. Everywhere you go on the web, with your phone or tablet, you’re a “user,” and your social network data will be mined every second by every application, site, and service to “enhance your experience,” as Facebook and others say. The tech industry’s leaders aim to expand this into the physical world, creating modulated advertising and environmental experiences as cameras and sensors track our movements.

Facebook and the rest of the tech industry fear autonomy and unpredictability. The ultimate expression of these irrational variables that cannot be mined with algorithmic methods is absence from the networks of surveillance in which data is collected.

One of Facebook’s preventative measures is United States Patent 8,560,962, “promoting participation of low-activity users in social networking system.” This novel invention devised by programmers in Facebook’s Palo Alto and San Francisco offices involves a “process of inducing interactions,” that are meant to maximize the amount of “user-generated content” on Facebook by getting lapsed users to return, and stimulating all users to produce more and more data. User generated content is, after all, worth billions. Think twice before you hit “like” next time, or tap that conspicuously placed “share” button; a machine likely put that content and interaction before your eyes after a logical operation determined it to have the highest probability of tempting you to add to the data stream, thereby increasing corporate revenues.

Facebook’s patents on techniques of modulating “user” behavior are few compared to the real giants of the tech industry’s surveillance and influence agenda. Amazon, Microsoft, and of course Google hold some of the most fundamental patents using personal data to attempt to shape an individual’s behavior into predictable consumptive patterns. Smaller specialized firms like Choicepoint and Gist Communications have filed dozens more applications for modulation techniques. The rate of this so-called innovation is rapidly telescoping.

Perhaps we do know who will live in the iron cage. It might very well be a cage made of our own user generated content, paradoxically ushering in a new era of possibilities in shopping convenience and the delivery of satisfactory experiences even while it eradicates many degrees of chance, and pain, and struggle (the motive forces of human progress) in a robot-powered quest to have us construct identities and relationships that yield to prediction and computer-generated suggestion. Defense of individual privacy and autonomy today is rightly motivated by the reach of an Orwellian security state (the NSA, FBI, CIA). This surveillance changes our behavior by chilling us, by telling us we are always being watched by authority. Authority thereby represses in us whatever might happen to be defined as “crime,” or any anti-social behavior at the moment. But what about the surveillance that does not seek to repress us, the watching computer eyes and ears that instead hope to stimulate a particular set of monetized behaviors in us with the intimate knowledge gained from our every online utterance, even our facial expressions and finger movements?

If you google “money,” the search engine called Google, from which that verbification is derived, will tell you that there are 1.12 billion results. That sounds like a lot of anything, but consider this fact: Google Inc. makes $1.12 billion in profit every 33 days.

If you google “money,” the search engine called Google, from which that verbification is derived, will tell you that there are 1.12 billion results. That sounds like a lot of anything, but consider this fact: Google Inc. makes $1.12 billion in profit every 33 days.