In 2012 Larry Ellison, CEO of the Redwood City-based Oracle Corporation, was awarded a compensation package worth ($96.1 million) nearly as much as the entire healthcare and pension costs of all BART employees ($101 million).

Are Bay Area Rapid Transit employees paid too much? It’s amazing that the question is even being asked. BART’s board of directors, general manager, and chief negotiator put this rhetorical query in front of the public during the strike two weeks ago as part of their strategy to undermine sympathy for BART workers. BART even set up a web site to spread it’s narrative of greedy employees, http://bartlabornews.com, where “Bart Rider” is soberly informed that “BART employees contribute $0 toward their pension plan, BART riders and taxpayers fund their retirement plans.” The point of public relations communiques like this are clear: in the Bay Area’s economy BART employees consume too many tax dollars and don’t have a legitimate need to maintain their existing pay and benefits.

BART management added pension and healthcare contributions to their tally of employee pay to claim that their employees “earn an average of $134,000,” even though pension and healthcare expenses are not cash equivalents for BART employees, and even though the healthcare expenses actually benefit BART as an employer by keeping their workforce healthy and productive. Even so most news outlets dutifully reported the average pay of BART employees and included health and pension costs as if this were cash, erroneously implying that the train system’s workers take home six figure salaries.

It’s amazing that the pay of BART’s employees has gained so much attention from the regional media in the first place. For over a decade the Bay Area’s major newspapers and TV news stations have been guilty of failing to adequately cover one of the most important stories of our time: rising income and wealth inequality, and the decline of middle class jobs in the face of inflation, globalization, automation, and the tax revolt that has scaled back the public sector. And now that most of the Bay Area’s news outlets finally reported a story about the pay of middle class public employees they bungled the story by framing it inside a question pre-packaged for them by an anti-labor consultant from Ohio: don’t BART employees make too much already?

The BART strike readily tells the big-picture story of austerity for millions of workers and exponentially growing incomes for the wealthy few. Let’s therefore re-frame the question of how much BART employees are paid and consider their compensation, its source and impact on the wider economy, to that of the top 1% of California’s income earners.

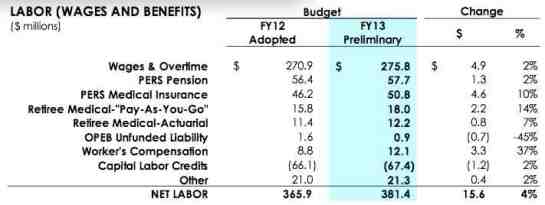

The average BART train operator has a base salary of $47,000, and takes home about $66,000 in cash when overtime is accounted for. Station agents have a base salary of $52,000 on average, and take home about $68,000 when overtime is included. Because BART employees have their healthcare and retirement costs currently covered, this means that their decent salaries are largely spent on housing, food, recreation, and other goods. All of this spending, including healthcare and eventually purchases made using retirement income, happens almost entirely within the Bay Area. What goes around, comes around, with $275 million in wages for BART workers fueling sales and profits for businesses in the Bay Area, feeding back into the budgets of other cities and local agencies.

Let’s now compare what BART employees make to the compensation of the region’s top one percent of income earners, the CEOs of Silicon Valley’s tech companies, and San Francisco’s financial institutions.

In 2012 Larry Ellison, CEO of the Redwood City-based Oracle Corporation, was awarded a compensation package worth ($96.1 million) nearly as much as the entire healthcare and pension costs of all BART employees ($101 million). Ellison has been raking in this kind of cash for decades and is one of the wealthiest men in the world. Last year he spent $300 million to buy an island in Hawaii. For that same sum of money Ellison could have bought every single BART train car and still had $44 million left over, enough to pay the overtime clocked by every single BART employee, and still he’d have $13 million left to buy a couple more trophy homes like his house on Broadway in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights, but truth be told in spite of the America’s Cup, most of Ellison’s fortune doesn’t get spent in the Bay Area. It sits in bank accounts, or is held as shares in corporations, or goes toward acquisitions of boutique real estate in distant enclaves of global wealth.

last year Ebay’s CEO John Donahoe was paid a lot more ($29.7 million) than all of BART’s 348 station agents combined ($23.6 million). His pay package could have covered their salaries and overtime, and picked up 2/3 of their healthcare and pension costs.

Wells Fargo’s CEO John Stumpf was paid ($19.3 million) almost enough to cover the total pension and healthcare costs of all BART train operators and station agents ($20.8 million), a combined workforce of 832 employees. It’s hard to imagine Stumpf spending even five or ten million in one year on groceries, transportation, and other goods from Bay Area businesses.

Meg Whitman, CEO of electronics giant Hewlett Packard, was paid ($15.3 million) more than double the total cash earnings of BART’s 131 utility workers ($6.4 million).

John Martin, the CEO of Gilead Sciences, was paid a bonus ($3.37 million) that exceeded the total healthcare costs of BART’s utility workers ($3.09 million).

So who’s paid too much? What is “enough” when it comes to the amount of money a person needs to live with dignity in California’s Bay Area.

Keep in mind that the above described levels of executive compensation are not determined by “natural” market forces. Nor are these spoils calculated by sober boards of directors mulling over the services these executives provide.

Pay at the top of the corporate food chain is as much a matter of culture, power, and politics, as it is the outcome of a supply and demand curve for managerial talent. That’s the lesson of the BART strike. The wages and benefits that will be afforded to BART’s employees are being struggled over in a political fight, not determined by mathematical economic principles.

When it comes to the eight figure pay packages afforded to CEOs today, on the culture side America has simply slipped further into an ethical quagmire that allows the polarization of classes between an elite few who are hoarding immense fortunes, and the many who live increasingly in debt. In political terms, those at the top of the economy engage constantly in their own version of collective bargaining, but instead of trying to wrest pay and benefits from management through unions, their focus is set instead on the U.S. federal tax code. As the management, holding the financial and legal resources necessary to lobby and influence legislators and regulators to write favorable legislation and to look the other way, these men (mostly they are men) have the power to often get what they want. And the decline of labor unions over the past four decades means that there is virtually no serious counter-force to fight them, to demand a more equitable economic regime.

The pervasive use of stock grants and stock options to pay company executives is now the top cause of massive pay packages for management, including those outlined above. Corporations shifted from simply paying their executives seven figure salaries to paying seven and eight figure stock grants and options packages when Congress disallowed tax deductions on salary expenses above $1 million in 1993. The law that disallowed deductions on salaries in excess of $1 million was an ethical rule resulting from the scandalous damages caused by excessive greed at the top of the economy in the 1980s and early 1990s. Management raided corporate wealth, crashed entire companies, and the response was to regulate the tax benefits they were gaming to enrich themselves.

Larry Ellison’s $96.1 million in pay primarily comes in the form of $90.6 million in options to purchase shares of Oracle Corporation at a set future date for a set price. One of the reasons companies like Oracle pay their CEOs this way is that they can deduct this sum from their federal corporate income taxes, along with bonus payments and stock grants. If a form of compensation other than base salary can be characterized as “performance-based,” then it can earn a corporation a tax benefit. Ellison’s compensation last year in the form of stock options therefore may have sliced upwards of $32 million off Oracle’s federal tax bill.

Ellison will have to pay taxes on his $90.6 million (or more if Oracle’s stock price outperforms the options pricing model they used to guess the value of the shares he may purchase), but until he exercises the options it’s all deferred. So last year Oracle and Ellison temporarily sheltered $90.6 million from the tax man.

When Ellison exercises his options he pays federal income tax on their value, and he’s likely in the top marginal bracket, but that bracket is at a historical low point. Massive reductions in income tax rates for the wealthy are part of the reason people like Ellison have become so enormously wealthy in recent years while the federal budget has run continuous deficits.

If Ellison holds the shares and they appreciate further in value, he can later sell them for a capital gain. Capital gains are taxed also at historically low rates of about 23.8 percent for the wealthiest handful of people like Ellison who currently own more than half of all stock in publicly traded companies. So although federal taxpayers supposedly “make up” for the loss of revenue deducted by Oracle when Ellison pays taxes on his stock options, the taxes Ellison is paying are quite low.

The other Bay Area CEOs you likely wont see riding BART because they can afford their own private jets are also paid mostly in the form of stock grants and options, creating valuable tax deductible expenses for their firms, and providing the executives with securities that can be held for years and sold for quite large capital gains.

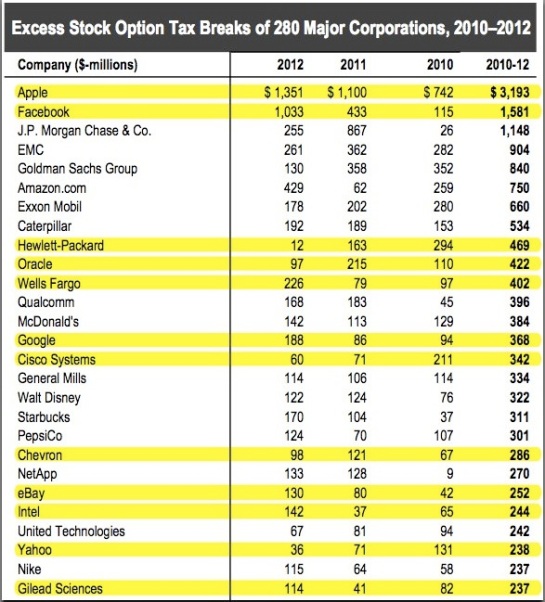

Earlier this year Citizens for Tax Justice, a research organization that studies inequity in the tax system, found that 280 of the largest U.S. corporations used stock option executive pay to reduce their tax bills by $27.3 billion over three years.

A good chunk of these deductions are potentially retained by corporate America as a kind of arbitraged profit because of the quirky accounting rules that allow them to basically guess the value of the stock they’re granting when they report their income to shareholders, but to then use the actual cost of the stock options to determine their eligible deduction when they’re exercised by the executive. The difference between that guess and the real price when exercised is all gravy. This quirk is entirely the product of lobbying by corporations and the wealthy to maintain a loop-hole permeated tax system set up for them to game.

Silicon Valley tech companies are among the biggest users of stock option compensation awarded to CEOs. Apple, Facebook, HP, Oracle, Google, Cisco and others therefore also reduce their federal taxes by billions each year. Source: Citizens for Tax Justice, “Executive Pay Tax Break Saved Fortune 500 Corporations $27 billion Over the Past Three Years,” April 24, 2013.

So what’s the connection back to BART?

A lot of BART’s funding for capital improvements comes from the federal government, and once upon a time transportation funds for operations were also available from the federal government, but these were mostly eliminated beginning in the Reagan administration. The loss of federal funds for operations and maintenance is a serious crisis for many of the nation’s bigger transit agencies like BART, and few think operations assistance will return due to the chronic federal budget crisis.

The squeeze on federal funds available for capital expansion also mean that transit agencies have to raid their own fares and tax dollars to come up with funds to pay for expansions. All of this creates the pressure that leads to the politics of austerity and demands that workers take cuts to shoulder more of the burden of funding public goods. When you zoom out and look at the entire system by which transit is funded, it’s clear that the political victories of the wealthy and corporate America to reduce statutory tax rates, and avoid taxes through numerous loopholes, sets the stage for conflicts between public sector workers, transit riders, and local government managers.

Bay Area’s Top Executive Pay in 2012:

Larry Ellison, Oracle Corporation

Salary: $1

Bonus: $3.9 million

Perks: $1.5 million

Options: $90.6 million

John Donahoe, Ebay

Salary: $970,000

Bonus: $2.8 million

Perks: $160,000

Stock: $23.7 million

Options: $2 million

John Stumpf, Wells Fargo

Salary: $2.8 million

Bonus: $4 million

Perks: $15,000

Stock: $12.5 million

Meg Whitman, Hewlett Packard

Salary: $1

Bonus: $1.68 million

Perks: $220,000

Stock: $7 million

Options: $6.4 million

John Martin, Gilead Sciences

Salary: $1.4 million

Bonus: $3.37 million

Perks:$7,500

Stock: $4.94 million

Options: $5.43 million

John Chambers, Cisco

Salary: $375,000

Bonus: $3.95 million

Perks: $11,000

Stock: $7.34 million