The failed economic policies of the Obama administration have been evident in measures of every important fundamental for six years now. Dismal job growth. High unemployment. Weak consumer demand, and so on. The biggest failure of the Obama administration was arguably the refusal to write down mortgage debt and force the top one percent of wealth holders to share some of the losses sustained during the housing market crash. While monetary policies pursued by the Fed, and a bailout of the secondary housing market with taxpayer dollars, temporarily provided a shot in the arm for housing prices, these gains were artificial. They weren’t based on genuine demand for housing by the majority of Americans. The result is that the top one percent of the U.S. housing market, the luxury segment, is booming, while the rest of Americans are having trouble affording homes. Now the housing market appears to be stalling out, except for luxury purchases by the elite whose wealth was protected by virtually every economic policy advanced through the financial crisis.

Let’s review the problem. In the 2000s the U.S. housing market was flooded with cheap credit. Lenders extended giant loans, many of them sub-prime, and the prices of houses shot upward in a bubble. But stagnating wages for American workers meant that the prices of real estate diverged from the reality of the ability of the average household to safely repay these loans. When the financial system imploded, the price of housing collapsed, and it was the borrowers who sustained the brunt of losses in the form of equity. The debt remained to be repaid, however, because Obama and his economic advisers chose to protect the wealth of the top one percent.

As economists Atif Mian and Amir Sufi have pointed out in their book House of Debt, the federal government could have taken over as the servicer of mortgage-backed securities and renegotiated millions of loans, dropping interests rates and principal balances. Or the government could have allowed bankruptcy judges to reduce mortgage debt burdens. The few principal reduction programs there were, like the Home Affordable Modification Program, could have been pushed much further. As is, programs like HAMP served only a small fraction of distressed borrowers with underwater loans. HAMP and other loan modification programs did not meet their original numerical goals.

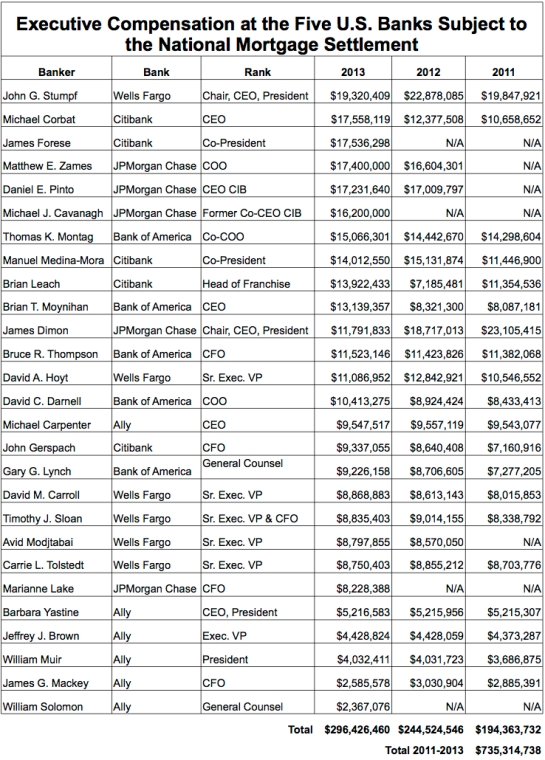

By not making creditors share the pain of the collapse of real estate prices, the Obama administration enforced a giant wealth transfer from the majority of Americans to a small minority, literally the one percent who own the majority of stocks and bonds, particularly stocks in banks and mortgage servicing companies, and bonds backed by residential mortgage debt.

But the wealthy also cache their fortunes in non-housing related stocks and bonds, and the Obama administration’s quantitative easing program has been good for supporting the value of these securities. So the wealthy never took the same kind of hit the average American did with housing price dips and job losses. Then the wealthy benefited from federal programs that jacked up asset prices.

Should we be surprised then to learn that the top one percent of the residential housing market is booming while sales of literally every home priced below a luxury-grade are dropping? This is one consequence of the Obama administration’s housing and economic policies.

A new batch of numbers from the real estate research firm Redfin illustrates the consequences of the Obama administration’s economic policies by comparing the very top of the American real estate market to everything else. “Sales of the priciest 1 percent of homes are up 21.1 percent so far this year, following a gain of 35.7 percent in 2013,” writes Troy Martin of Refin. “Meanwhile, in the other 99 percent of the market, home sales have fallen 7.6 percent in 2014.”

“For the top 1 percent, the housing market is still booming. But for the rest of the market, the recovery is running out of gas,” concludes Martin. “As home prices have risen, wage and job growth have failed to keep up.”

Redfin’s research shows that in virtually every major metropolitan region the luxury segment of the housing market, the top one percent of homes in price terms, are selling fast and at higher prices. Not surprisingly, there’s considerable regional variation, but it’s a nation-wide phenomenon.

The real estate market in the San Francisco Bay Area is perhaps the most unequal and driven by sales to the super-rich. Luxury home purchases are way up in Oakland, San Jose and San Francisco, with Oakland and San Jose experiencing a virtual doubling of the luxury market over the past year. The top one percent of the market for Oakland, San Jose and San Francisco combined is priced at an average of $3.7 million, but San Francisco has pulled ahead of the rest of the nation with an average home price of $5.35 million for the top one percent of its market. Some of this is likely due to the booming tech sector which is creating thousands of millionaires in the region.

For the majority of Americans the problem boils down to household debt. There’s still too much debt for the average household to sustain purchasing power that would drive an economic recovery, including a recovery in the housing market. From 2003 to the peak of the housing bubble in the third quarter of 2008, total household debt shot upward by about $5.4 trillion, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. From the peak of the housing bubble to the present, total household debt only decreased by $1.5 trillion. That means that about $3.9 trillion in debt piled onto U.S. households during the housing bubble is still weighing down family budgets. Most of this debt, about $2.89 trillion, was mortgage debt.

For the majority of Americans the problem boils down to household debt. There’s still too much debt for the average household to sustain purchasing power that would drive an economic recovery, including a recovery in the housing market. From 2003 to the peak of the housing bubble in the third quarter of 2008, total household debt shot upward by about $5.4 trillion, according to data compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. From the peak of the housing bubble to the present, total household debt only decreased by $1.5 trillion. That means that about $3.9 trillion in debt piled onto U.S. households during the housing bubble is still weighing down family budgets. Most of this debt, about $2.89 trillion, was mortgage debt.

Over the same time period wages remained flat for most Americans. The median household incomes in the year 2000 was approximately $42,000. In 2012 it was about $51,000. Accounting for inflation, the real value of household income actually declined over this period by $5,000.

The income and wealth gains at the top of America’s economic pyramid over this same time frame should be familiar by now, as they have been extensively explained in recent research. What’s important to point out, however, is that the the average household, the median Americans whose incomes dropped by $5,000, took on significant mortgage debt during the 2000s, altogether in the trillions of dollars, and the lenders of this capital, ultimately, are the top one percent households.

So that’s why we see the luxury housing market booming while virtually 99 percent, the rest of America is stagnating.