Easily the biggest winners of this year’s World Series are the owners of the San Francisco Giants baseball club. The Giants franchise is owned by a limited partnership called San Francisco Baseball Associates, L.P. There are 32 partners invested in the club, but it’s widely understood that most just possess a couple million in share equity, while a few hold the controlling shares. None of the owners are purported to be very active in the team’s management except Lawrence Baer, a minority owner and president and CEO of the club.

Easily the biggest winners of this year’s World Series are the owners of the San Francisco Giants baseball club. The Giants franchise is owned by a limited partnership called San Francisco Baseball Associates, L.P. There are 32 partners invested in the club, but it’s widely understood that most just possess a couple million in share equity, while a few hold the controlling shares. None of the owners are purported to be very active in the team’s management except Lawrence Baer, a minority owner and president and CEO of the club.

Share values in the Giants partnership have grown enormously since roughly two-dozen investors bought the baseball club in 1992 for about $100 million. At last estimate the Giants franchise was valued at $643 million. With their second World Series title in under three years sealed and their fan-base rapidly growing, that price is likely to have shot up. So who exactly is getting rich?

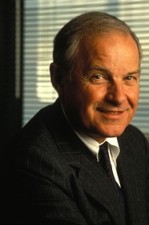

Charles B. Johnson

The largest Giants shareholder is Charles B. Johnson, estimated net worth of around $4-5 billion. That makes Johnson the wealthiest man in baseball. Whatever money Johnson has made off the Giants is small potatoes compared to the fortune he started with.

Johnson’s money comes from Franklin Resources, a mutual fund company his father founded. Johnson is pretty much Bay Area royalty, about as elite in both the social and economic sense as they come. He’s a trustee of Stanford’s conservative Hoover Institution, and has been a member of the corporate policy lobbying group the Bay Area Council.

Johnson lavishes money on conservative, anti-labor causes and political candidates. Just this year Johnson gave $200,000 to Karl Rove’s American Crossroads super PAC, and $50,000 to the pro-Mitt Romney Restore Our Future super PAC, in addition to many other causes. Johnson is also the largest funder of the campaign against California’s Proposition 30 which would raise taxes on the super wealthy to fund education; he gave an anti-30 committee $200,000. Johnson has also contributed $50,000 to Proposition 32, the California ballot initiative that would virtually ban union money in California politics.

Charles B. Johnson’s home, the Carolands Chateau in Hillsbourough, CA.

Earlier this year Johnson held lavish fundraising events for Mitt Romney in his opulent Hillsborough mansion, the Carolands Chateau. In previous years Johnson invited George W. Bush to hold fundraisers at Carolands also.

Charles Johnson’s partner in business at Franklin Resources, a man named Harmon Burns, was until 2006 the largest share owner of the Giants. His death in that year passed his shares on to his wife, who then died in 2009 leaving the stake to be split between their daughters, Tori and Trina. In other words, majority ownership of the Giants rest with three people whose fortunes come from the Franklin Resources, Inc. company.

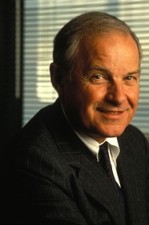

Peter Magowan, the Giants’ former managing partner who is credited as the catalyst for bringing the current group of owners together to buy the team in 1993, remains a large shareholder. Like his fellow owners, Magowan’s money doesn’t originate in baseball. And like more than a few of his fellow owners Magowan inherited his fortune. Magowan also shares the conservative, anti-labor values of some of his fellow Giants owners.

Peter Magowan (picture from Caterpillar, Inc.’s web site).

His grandfather was the founder of the investment bank behemoth Merrill Lynch (now part of Bank of America) and also a founder of the Safeway Corporation. Magowan’s father ran Safeway, and Magowan himself was elevated to the position of CEO of Safeway in 1979. By then the company had become the supermarket titan it is today.

Like Charles Johnson, Peter Magowan is a reactionary conservative who actively throws money against social justice causes. Magowan has lavished hundreds of thousands of dollars on Republican Party candidates John McCain, Carley Fiorina, and Paul Ryan. Earlier this year Magowan gave Karl Rove’s American Crossroads a $75,000 contribution toward defeating Barack Obama and other Democrats in key states, as well as $25,000 to the Restore Our Future super PAC. Earlier this year Magowan gave Wisconsin governor Scott Walker a $10,000 contribution to fight the recall campaign initiated against him by labor unions after Walker attempted to abolish collective bargaining.

Magowan is known as an anti-union corporate manager from his earlier years running Safeway. When Safeway was taken private in an LBO orchestrated by KKR in 1986, Magowan led an effort to bust up unions inside the company and drive down wages so as to drive up profits for the new private equity owners. “Our intention is to discuss with the unions those divisions that are having profitability problems, in our opinion entirely because of the fact that we pay higher labor costs than our competition in several markets that we operate,” Magowan told the LA Times during the company’s restructuring.

In addition to his current ownership stake in the Giants, Magowan also sits on the boards of Caterpillar, Inc. and DiamlerChrysler. Caterpillar has been widely criticized for selling bulldozers to the Israeli government through U.S. Foreign Military Sales Program. These bulldozers are used to demolish the homes, businesses, and farms of Palestinians.

The Giants owners aren’t just conservative tycoons. Among the minority owners of the Giants are some Democrats also. Giants owner Philip Halperin runs the Silver Giving Foundation, a philanthropy he created with money he amassed while working as a partner in the Weston Presidio private equity firm. Halperin’s official biography on the Stanford Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies web site (where he sits on the advisory board trustee) says that at Weston he was, “focused on information technology, consumer branding, telecommunications and media,” and that he “previously worked at Lehman Brothers and Montgomery Securities.”

Halperin contributes relatively small amounts to the Democratic Party and candidates in any given year. He also sits on the board of Autonomy Virage, a company that specializes in developing surveillance systems for corporate and military clients.

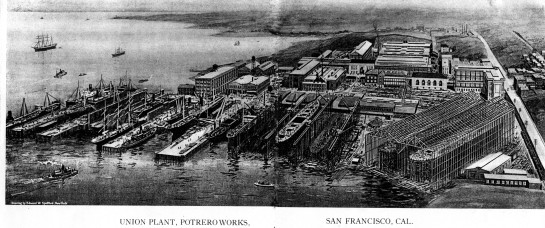

More than several of the Giants minority owners are real estate tycoons, a fitting source of wealth given that the Giants baseball franchise itself has been a major force in a broader effort by San Francisco’s landlords to further gentrify the entire city and drive up land values. The Giants’ downtown stadium seamless connects the financial district (the product of 1960s and 1970s urban “renewal”) with China Basin and Mission Bay. The latter areas have seen enormous real estate investment in the 1990s and 2000s, including numerous luxury condo and high-rise apartment projects ringing the AT&T Park and the University of California’s brand new medical school campus (around which biotech companies are in a frenzied push to claim land).

Some of the Giants’ current owners have been keen to cash in on this speculative frenzy. An article from a 1997 issue of the San Francisco Business Times describes one case:

“In March, Allan Byer, a minority partner of the San Francisco Giants and owner of the Byer California clothing manufacturing company, beat out three other investors to plunk down $3.15 million for an aging and empty brick warehouse at 128 King St. On paper, the deal makes little sense. According to the San Francisco Tax Assessor’s office, the building is worth just $316,194. Why pay 10 times that much for an old building that hasn’t earned a dime in decades? The answer lies directly across the street, where in the middle of November, the Giants will hold a groundbreaking ceremony to start construction of PacBell Park, the team’s new 42,000-seat stadium. On opening day in April 2000, tens of thousands of people will stream into the stadium for the game, most of them passing directly in front of Byer’s property, which by then likely will house two or more restaurants — tables packed and cash registers humming.”

Other big shot real estate investors who own minority stakes in the Giants include David S. Wolff of the Wolff Companies, and Scott Seligman of the Seligman Group. Wolff controls a huge portfolio of Houston office properties.

Scott Seligman’s company owns the Sterling Bank & Trust, and numerous office properties in California, Nevada, and Michigan. Seligman has been singled out as the ugly face of gentrification in San Francisco by non other than Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the famed poet and owner of City Lights books. Back in 2001 Seligman was in the process of evicting tenants from a building he controlled in the Mid-Market area (the same part of San Francisco now being colonized by Twitter thanks to a big tax break the Board of Supervisors gave the company). In a press release Ferlinghetti lashed out:

“A developer from Michigan, Scott Seligman, who runs Sterling Bank and Seligman Western Enterprises, wants to gentrify the Mid-Market zone. Not to make the City a better place but to make his bank account a little fatter. He wants a better class of tenant. No more photographers or poets or translators or editors or painters. No more small businesses serving the City. No more small nonprofits, like Streetside Stories, which publishes work by 650 middle school kids every year to foster a love of reading and writing.”

Ferlinghetti was trying to draw a line: “It’s long past time for San Francisco—the people who live here and care about the place, the politicians, the small businesses, the kids who will inherit either a theme park or an exciting, urbane City—to stand up and stop the development juggernaut.”

AT&T Park from the air, obviously a jewel in king gentrification’s crown.

Of course the development juggernaut stumbled for a couple years, but then raged on. The Giants new ballpark was a key piece in advancing the juggernaut not only because it linked gentrifying regions of the city, but also because it secured a much desired form of high-priced entertainment for the tech and finance employees quickly populating trendy neighborhoods like Soma and the Mission. These highly paid, college educated urban pioneers have driven out thousands of long-time residents, mostly Black and Latino families whose existence sullies the theme park atmosphere, and who can’t pay the rapidly rising rents making men like Seligman very wealthy.

Meanwhile tickets to a Giants baseball game have shot up in price, making an outing to even the most mundane mid-season match too costly for some San Franciscans. Ball games have become something of a posh affair. The restaurants that ring AT&T Park are pricey, as is the food and drink inside the games.

Nowadays many of Silicon Valley’s big companies —Google, Yahoo, Facebook— send fleets of company buses into San Francisco’s hipster enclaves like Noe Valley, the Mission, Bernal Heights and Soma to pick up their twenty to forty-something year-old engineers and code geeks, shuttling them on these private transit systems directly to work with onboard wi-fi and other so-called perks to keep them satiated. In the 1990s it was no surprise that the young workforce fueling California’s booming technology capital wanted to live in an exciting city and shunned the quiet suburbia of Palo Alto, Cupertino, and Santa Clara. They wanted city lights, “gritty” urban experiences, 2 AM burritos on 24th Street, over-priced coffee along Valencia, art galleries on Natoma, endless music and clubs, and yes, of course they’d want baseball. Most importantly, they’d be willing to shell out hundreds of dollars or more every year for tickets.

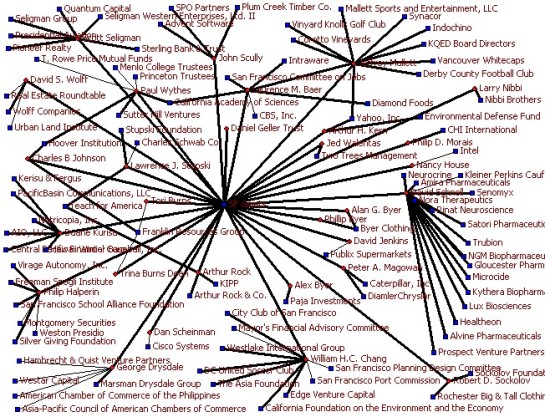

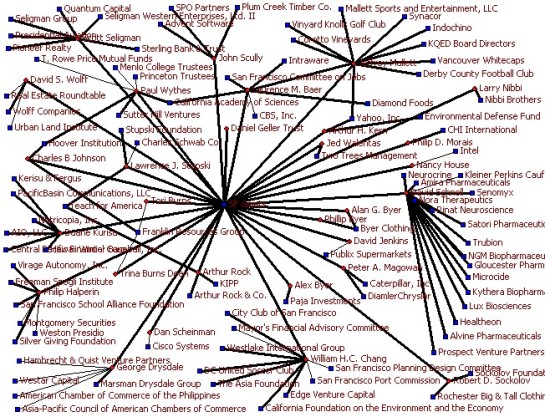

The owners of San Francisco Baseball Associates, L.P., and the companies, foundations, and non-profit corporations they control, own, or direct.

So it should be no surprise that filling out the minority owners of the Giants baseball club are mostly technology executives. They had both the money to burn thanks to their IPOs and buyouts, and they had the larger reasons of class interest to make what was seemingly a philanthropic investment in the 1990s when the Giants almost left San Francisco for Florida. The team’s majority owner back then complained he had been losing money after voters thrice rejected his efforts to get public funds to build a new stadium. Many observers thought the new owners were simply sacrificing a few million to keep the team in San Francisco; the Giants were also a pretty mediocre ball club then, and attendance at games, held out at the windy Candlestick Park, wasn’t the greatest. When the new owners took over they ended up getting millions in public subsidies to build the new downtown stadium by the water. Even though they claim to have been the first franchise to “go private” with ballpark financing, the Giants’ owners did in fact receive at least $80 million in infrastructure upgrades paid for by taxpayers. The stadium also sits on public land, leased to the Giants at a very cheap rate.

Of course the new owners weren’t philanthropists. They were operating as sharp business executives. The baseball club was a keen real estate investment, and a very strategic investment toward their larger project of keeping San Francisco hegemonic in the tech economy. This larger vision of urban development has involved rapidly eradicating working class communities and replacing them with yuppified landscapes populated by mostly white college educated newcomers. Surprisingly few in San Francisco have consistently criticized the Giants baseball club for playing a key part in this harsh gentrification campaign executed on a city-wide level.

In 2011 Bachher co-authored a paper about investment opportunities across the economies of Alberta, China and India. Bachher focused on investments in energy, calling Alberta a “veritable bank vault of natural resources,” meaning mostly oil and gas.

In 2011 Bachher co-authored a paper about investment opportunities across the economies of Alberta, China and India. Bachher focused on investments in energy, calling Alberta a “veritable bank vault of natural resources,” meaning mostly oil and gas.