The Collapse of Michigan’s Largest City Parallels a Long Campaign to Undermine Labor Radicalism and Racial Integration

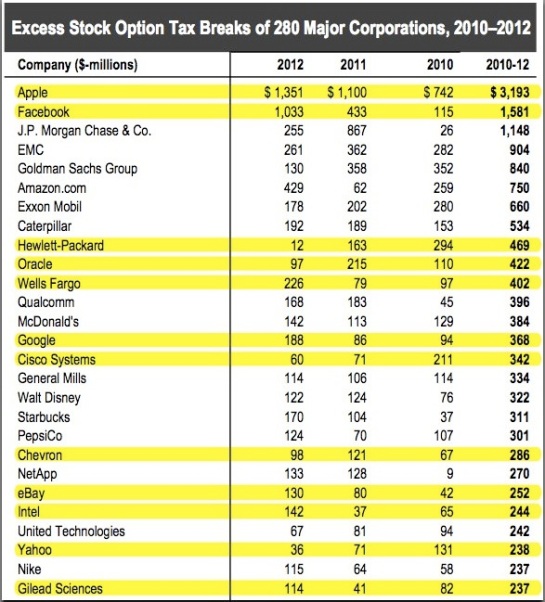

Underneath all the economic and political symptoms there are really only two causes of Detroit’s fiscal collapse that recently culminated in bankruptcy. The first cause of the Motor City’s decline is corporate America’s merciless, and quite successful campaign to annihilate labor unionism, especially the more radical variants. This of course reverses the conservative myth that Detroit was done in by “greedy unions.” Far from it. Detroit was done in by wealthy corporations that divested capital from the region in order to pry bigger profits from their workers, be they in the Midwest, or in the US South and Mexico.

The second cause of Motown’s chronic poverty is white racism – not the discriminatory variety whereby some white people treat African Americans unfairly and unkind, but rather the structural and political anti-Black policies and practices around which government and the private economy are still largely organized today.

Combined, the corporate attack on organized labor, and popular white revanchism to thwart the economic goals of the Black freedom movement have devastated Detroit. The victims are the city’s poor, mostly African Americans, but also a small number of impoverished whites and Latinos who have seen essential services disappear. Of course corporate America’s campaign to undermine organized labor wasn’t confined to Detroit and Michigan. Nor was white America’s exodus from the urban core behind suburban units of exclusionary local government. But the results are clearer today above and below 8 Mile Road, the 8 lane asphalt border separating Detroit from its suburbs, than virtually anywhere else in the nation.

As the “arsenal of democracy” in the early 1940s, Detroit was turning out more war materiel and weaponry than probably any other city on earth. Several hundred thousand southerners arrived in Michigan during the war to take jobs in the mega-factories that were expanding along the River Rouge, in Hamtramck, and on the banks of Detroit River. After the war most of the tank and bomber assembly lines were converted back to auto manufacturing and other civilian machinery, but Detroit kept a good share of the nation’s multi-billion dollar weapons contracts throughout the Cold War. Such are the complex contradictions of America’s rise to global military and economic power; the working class who built the war machine and produced unimagined quantities of consumer goods, fueling one of the world’s greatest historical accumulations of capital, umbrellaed by the Pentagon’s unrivaled ability to project power, were also fostering a culture of labor radicalism.

Marx described the process a century prior. Capital would create the conditions for its own demise on the vast shop floors where toiling workers would find solidarity and organize. Capital’s intellectuals have long recognized the dynamic also, but instead of writing mechanistic theories of how the revolution from private ownership to social democracy would naturally unfold, they were busy making plans to undermine the threat.

In the late 1940s and 1950s Detroit teemed with communists, socialists, anarchists, and other anti-capitalists, in addition to hundreds of thousands of militant workers with no particular ideology straitjacketing them. They all had more than enough gumption to challenge their bosses. A massive wave of strikes roiled Detroit in the post-War period, so many that one local newspaper ran a “strike box score” like that which keeps track of hits and runs in baseball. Detroit’s industrial working class became a core of the US labor movement in the 1950s. The city’s cavernous auto plants became battlegrounds not over mere working conditions and pay, but over ideology, and over control of the American economy. Workers demanded a hand in directing investments and planning production. Radicals attempted to inspire and mobilize the workers to move beyond narrow business unionism, to build a lasting counter-force to capital on the national political level.

Civil rights movement organizations forged alliances with Black and white workers to address racism within the unions, and to attempt what has proven elusive throughout American history, to build a multi-racial front for economic democracy. The auto plants were eventually desegregated, as were other industries, and in time the most powerful unions in the United States were integrated, but at the same time the racial and class ideologies that would unravel labor solidarity were poisoning the air.

Most whites actively resisted residential de-segregation, or did nothing to undo the shift from de jure racism to structural racism. A sign in suburban Detroit in the early 1960s.

Socially and geographically many whites in Detroit built walls of exclusion around their residentially segregated housing, their better schools, their better endowed financial and insurance institutions, their hospitals, and their private clubs. They were doing what white workers, rising into the so-called middle class, were doing in virtually every corner of the United States. Racism, the complex means of organizing society around white privilege, remained an appealing political program to many white workers in spite of the gains they made with their Black brothers and sisters in the factories.

By the late 1960s white Detroit was already staging an exodus from the city into the rapidly growing suburbs of Oakland County, and the transformation of the US into a post-industrial services and knowledge economy would be seized by these well-positioned white suburbanites. Black Detroit, still only one generation removed from the plantations of Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia, lacking the social capital and racial pass card of access to economic rights were trapped in Motown. The rebellion of 1967 against the city’s mostly white police force and political establishment revealed the raw racism that was tearing the region’s working class apart. Many white Michigan residents supported a crack-down on the Black communities, un-moved by the root causes of the rioting.

In the suburbs of Oakland County and a handful of affluent cities and townships in Wayne County many white Michigan families made the leap from the industrial era into an economy dominated by healthcare, computing, finance, real estate, engineering, insurance, and research and education. Whites in the exurbs of the Detroit metropolitan region became one of the most affluent populations in the United States. More than half of Black Detroit found itself blocked, unable to access and afford the means of social mobility. Black Detroit became one of the poorest populations in the United States, afflicted by the social ills of violence that grow from severe inequality.

Disproportionately, Blacks in Detroit experienced rapid downward mobility. Their salaries, healthcare, and pensions provided from employment in the factories were replaced with minimum wages and no benefits in the growing service sector of restaurants, retail, and hospitality. That’s if they could get a job at all. Unemployment grew steadily in Detroit. The jobs their fathers had once held in the auto plants, machine shops, and other factories across the region were now held by minimally paid southern laborers without union protections, or else by Mexican and Asian workers in the expanding maquiladoras of the global south.

Detroit’s population shrank mostly from the white out-migration to cities and towns like Royal Oak, Grosse Pointe, Birmingham, Troy, Franklin Village and dozens of other independent local governments with their own tax bases, budgets, and school systems. Detroit’s 1.6 million people as of 1960 dwindled to 1.2 million by 1980. It fell again to 950,000 in 1990, and has cratered at just above 700,000 today.

A mansion in Bloomfield Hills, Oakland County, Michigan. Bloomfield Hills is one of the wealthiest communities in America. In 2009 the Wall Street Journal listed this home as a “bargain” for the price of $4.95 million.

The city of Troy, incorporated in 1955 in Oakland County just eight miles north of 8 Mile Road, the physical and psychological border of Detroit, grew quickly in the latter half of the 20th Century into an affluent, majority white community. Dozens of other exurban enclaves, most of them smaller, quite a few home to the region’s new elite, grew over the same period.

In a sense whites, and later a small group of Black middle class migrants exited Detroit with the social and economic capital they acquired at the height of the city’s industrial flower. It was like a run on a bank that causes the institution to implode. Detroit’s affluent residents took the human and financial capital of what was once one of the wealthiest cities on earth and they redeposited themselves and their savings beyond the reach of the struggling city.

Of course the reasons to leave were ample. Dozens of major manufacturing plants in and around Detroit were closing and entire sections of the city were becoming not much more than tracts of housing for jobless laborers with little savings. The American auto industry shuttered much of Michigan’s manufacturing plant (and much of the Midwest’s) in the 1970s and 1980s in the face of cheap Japanese imports. However, the flight of capital from Detroit can actually be traced back before this threat from “globalization.”

It’s clear from the political literature written about Detroit that America’s ruling class saw the shop floors of Ford, GM and Chrysler as dangerous agglomerations of race and class conscious labor. Workers in the Midwestern manufacturing sector were very much responsible for the immense gains that most American workers obtained in the post-war period until about 1970. Beginning with the bloody strikes of the 1930s and reaching through into the 1950s labor militancy in Detroit and the rest of the Rust Belt forced America’s corporate titans to share the national income and accept a more democratic society.

To break the back of labor unions in America the major corporations and financial companies broke Detroit. Over the long-haul capital withdrew from the region’s manufacturing infrastructure and poured instead into the un-unionized American South, and overseas into Asia and along the US-Mexico border. The Detroit metropolitan economy reconfigured itself around the suburban office parks of Oakland County, and the wages of whiteness prevailed over the brief post-war possibilities of multi-racial solidarity.

Police sports cars, one of many signs of conspicuous public sector consumption in Oakland County’s affluent suburban cities and towns.

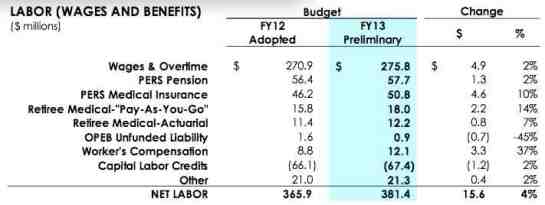

Because of the highly fractured system of independent local cities, counties, and revenue authorities that characterizes American government this demographic shift translated into a permanent fiscal crisis for Detroit. Big public pension obligations, or none at all; corrupt mayors, or squeaky clean politicians; it didn’t really matter. These influences on Detroit’s fate weren’t sufficient, nor necessary to cause the collapse. It was capital and white flight that did the city in. The tectonic shift in incomes and wealth reduced Detroit to the status of a revenue-starved city retaining all its responsibilities of social investment and a much amplified welfare load. The city was prevented from annexing nearby suburbs where retail tax dollars were being captured, and where real estate prices where rising along with family incomes. The region’s affluent suburbs and the state government refused systemic reforms for revenue sharing across governments. White Michigan and the new corporate community, largely ensconced in the suburban and rural regions of the state, sat back to watch the urban core burn.

8 Mile Road slices across Detroit’s northern border, geographically and fiscally severing the city from the tax bases of wealthy towns and cities to the north.

An analysis of Detroit and 28 of the independent suburban towns and cities above 8 Mile Road, mostly in Oakland County, shows clearly how the massive, unsustainable debt came about. Just between 1999 and 2011 the annual median household income for Detroit’s residents fell by $4,300, from $29,500 to $25,100. The number of unemployed doubled from 7.8 to 15.5 percent of the adult population, with many of these job losses resulting from the 2008 financial crisis.

A handful of the Oakland County suburbs, mostly those bordering the city along 8 Mile Road also saw the incomes of their residents drop, and joblessness rise causing fiscal problems for these governments also. The rest of Oakland County prospered over the same period, however.

For example, the aptly-named Beverly Hills, a small incorporated village about 7 miles from Detroit has seen the median family income of its residents grow by $12,700 over the last twelve years, from $90,300 to $103,100 today. In a few other Oakland County enclaves families register incomes more than double the nation’s average, three times that of Detroit. These cities, towns, and villages, many of them incorporated in the 1950s and 1960s expressly to absorb white migrants bailing from Detroit, are fiscally healthy units of government. Oakland County today maintains a AAA bond rating from Moody’s and uses this to finance many of the smaller townships, villages, and school districts in its limits. Bloomfield Hills School District has maintained a AAA credit rating thanks to its wealthy residents who are solidly in the top 20 percent of US income earners. Ratings on much of Detroit’s paper ranges from speculative to junk status, often with “negative outlooks,” a phrase in the industry that means downgrades are likely.

Detroit’s unraveling is far from over. The bankruptcy process instigated by emergency manager Kevin Orr is designed to kill off one last vestige of political and economic power of the city’s working class – the defined benefit pension obligations of public employees. Finally, if and when Detroit’s regimen of austerity comes to an end, renewed investment in the city is likely to come in the form of waves of gentrifying housing and commercial development which may cause mass displacement and provide few benefits to the city’s working poor as the jobs created will be more of the same precarious service industry roles.