How do judges reach conclusions in complex cases where the law is often open to interpretation, or where the laws are still changing in response to the times? Are judges influenced by cultural currents? Do politics sway their decisions? What role does their material interest play in shaping their rulings and legal reasoning?

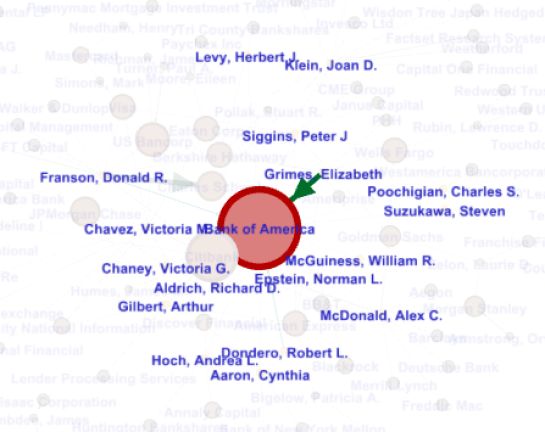

A network diagram of the 42 of California’s 105 Appellate Court judges who own at least $2,000 of stock or bonds in a financial company. The larger and darker colored nodes are financial companies. The node size is based on the number of judges who reported an ownership stake in the company. The larger the line connection two node (judges to their investments), the larger the investment in dollar terms.

I don’t claim to have answers to any of these questions. But in searching for some possible reasons for the outcomes of homeowner lawsuits against banks, mortgage lenders, and mortgage servicing companies in California, I thought it might be useful to compile information on the economic interests of the judges themselves. The advantage of focusing on the economic interest of judges, as opposed to other factors that shape their interpretations of law, like political ideology or culture, is that material economic interests are literally material, and therefore easily identified and measured.

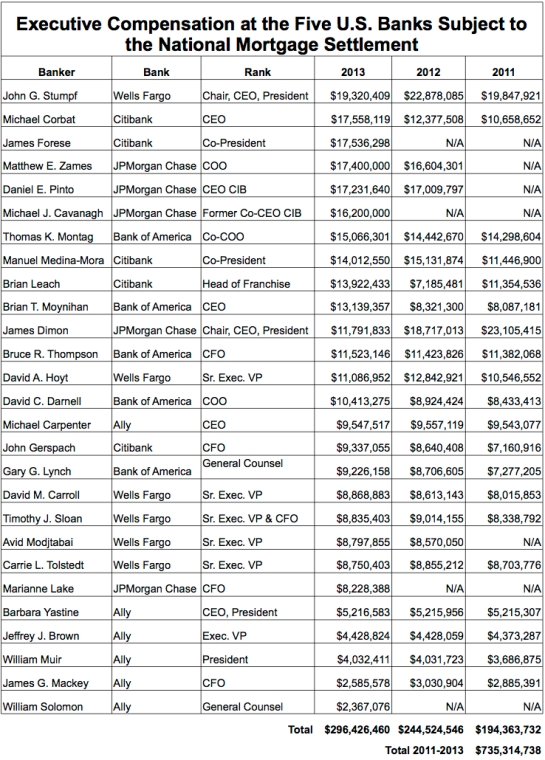

17 California Appeals Court judges reported owning at least $2,000 of stock or bonds in Bank of America, the most of any financial company. Bank of America is one of the largest mortgage lenders and servicers in the U.S., and has been frequently sued by California homeowners over alleged fraudulent and deceptive business practices, and wrongful foreclosure. Justice Elizabeth Grimes reported owning between $100,000 and $1 million of stock in Bank of America in 2012, the most of any judge. Altogether these 17 judges reported owning as much as $2.3 million of Bank of America securities.

Citibank was the second most commonly held financial company investment by California’s Appeals Court judges. 10 justices reporting owning at least $2,000 in stock or bonds.

From 2008 to the present California’s courts have been swamped with lawsuits, many more than in prior years, contesting foreclosures. Most often the plaintiffs have been homeowners suing banks and mortgage servicers over the foreclosure process. The banks have also initiated lawsuits against each other, against businesses, and against homeowners.

I haven’t done the research that would allow me to discern whether or not the banks are winning more than borrowers, but what I’ve heard from plaintiffs’ lawyers is that they feel the justice system has been biased in the favor of large financial companies. Lawyers and homeowners say that the courts favor the interests of creditors over consumers. Has anyone compiled comprehensive statistics on the outcomes of lawsuits between banks and borrowers through the financial crisis? I’d love to see that data set.

Judge Donald Franson of the 5th District Appellate Court reported owning stocks or bonds worth significant amounts in multiple banks as well as in the Och-Ziff hedge fund (which was briefly financing a foreclosure to rental business), the credit card powerhouse VISA, and Warren Buffet’s conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway (which owns a bank, a real estate firm, and other real estate and financial sector companies).

One theory to explain what homeowners and their lawyers perceive as judgements biased in favor of financial companies involves the material interests of the judges. In the most direct sense, many judges own stocks and bonds in mortgage lending and servicing companies, and so these judges might be biased in favor these same companies when they are sued by borrowers. Judges should recuse themselves from cases in which they have a financial interests in the profitability of one of the parties before them, but they sometimes don’t. Recusal is meant to avoid any actual biased options stemming from conflicted interests on the part of the justices, but it’s also supposed to prevent even the perception of a conflict of interest. Perception that justice system is fair is as big a deal it seems as the actual fairness of outcomes, however you might measure the latter.

Justice Arthur Gilbert of the 2nd Appellate District Court disclosed owning stock in three of the largest national banks that dominate the mortgage lending market, as well as having owned a financial stake in Lender Processing Services, a small specialized financial company that describes itself as “a leading provider of mortgage and consumer loan processing services, mortgage settlement services, default solutions and loan performance analytics.” Gilbert has sat on appellate panels hearing foreclosure lawsuits pitting banks and mortgage servicers against homeowners.

A more nuanced version of this conflict of interest theory has it that judges are ideologically influenced by their class position as high income earners, and holders of considerable wealth, a lot of which is invested in the securities of the major banks, and the mortgage lending and servicing companies. Quite a few of California’s Appeals Court judges are millionaires and they vest their wealth in stocks and bonds of large blue chip companies, often ones that pay hefty dividends. The financial sector is a major investment target for judges, and its biggest banking and mortgage lending companies pay them hefty dividends. Under this theory, even if a judge doesn’t hold stock directly in a financial corporation that argues a case in their court, judges are believed to be influenced by their general interest in the banking and mortgage lending sectors of the economy. Judges are said to exhibit bias in favor of the banks, and to respond to borrowers’ legal arguments with a weary skepticism as rulings in favor of borrowers could upset the appreciation of stocks and the yields on bonds of the entire financial sector.

Lastly it should be noted that financial companies are probably not the largest targets of investment by California’s Appeals Court judges. If ranked by the upper end of the disclosed range of investment, finance and banking falls after tech, energy (mostly oil and gas), consumer products, industrial manufacturing, and diversified funds (including private equity, mutual funds, bond funds, etc.) as a sector of the economy where judges like to seed their wealth.

| California Appellate Court Judges Ownership of Securities, by Sector of the Economy, Reported as of 2012. | ||

| Sector | Low Est. | High Est. |

| Technology | $3,214,000 | $31,620,000 |

| Energy | $3,902,000 | $27,560,000 |

| Consumer Products | $2,474,000 | $24,270,000 |

| Industrial | $3,272,000 | $22,960,000 |

| Funds | $3,984,000 | $21,770,000 |

| Finance, Banking | $4,034,000 | $21,270,000 |

| Retail Stores | $914,000 | $8,820,000 |

| Pharma & Biotech | $804,000 | $7,770,000 |

| Telecom | $752,000 | $7,260,000 |

| Real Estate | $1,586,000 | $6,780,000 |

| Healthcare | $386,000 | $3,680,000 |

| Entertainment & Hospitality | $550,000 | $3,400,000 |

| Utilities | $328,000 | $3,240,000 |

| Government Bonds | $240,000 | $2,400,000 |

| Misc | $226,000 | $2,230,000 |

| Consulting | $166,000 | $1,630,000 |

| Agricultural | $142,000 | $1,410,000 |

| Insurance | $114,000 | $1,070,000 |

| Mining | $96,000 | $930,000 |

| Media | $68,000 | $640,000 |

| Logistics | $64,000 | $570,000 |

| Transportation | $34,000 | $320,000 |

| Total |

$27,360,000 | $201,700,000 |