Part of San Francisco’s Union Square hyper-lux retail offerings, the De Beers store which features armed guards at the entrances. Ferrari recently opened a store a block away on Stockton Street. Haute Couture names obscure fill the district’s buildings offering items of conspicuous consumption.

Through the Financial Crisis and the Great Recession, inequality has intensified through income, housing, and public debt in the Bay Area. Black and Latino communities have lost wealth and power, while white and Asian communities have mostly to recovered. At the top, the wealthiest 5 to 10 percent, have made enormous gains.

Imagine a place where the hills are lined with the mansions of millionaire families, some of them billionaires. Their residences sit atop forested ridge lines with views of a peaceful ocean, or upon oak-studded peninsulas that jut into an azure bay. In this place they want for nothing. De Beers opened a retail store in one of their favorite shopping districts a few years ago, next to haute couture names like Bulgari, Cartier, and Gucci. An investment bank opened a “coffee shop” just a couple blocks from the headquarters of no less than seven Fortune 500 corporations, to catch their employees after work for talks over lattes about what to do with all that money crowding their bank accounts. Posh towers filled with luxury apartments sprout from the city center where multiple cranes seem to perpetually dot the skyline. iPhones pop from the palms of pedestrians like third hands, and newfangled apps like third eyes give them instantaneous information about the latest opulent consumer activities. Everything glows with money and power, a lot of it.

Below the hillsides glittering with wealth are even more expansive terrains of crumbling homes and apartment buildings —many foreclosed upon and awaiting some kind of financial death— packed with families that barely scrape together twenty thousand dollars a year to live on. Their views: smokestacks, port cranes, freeway overpasses, and scrap yards, or, sometimes on a clear day, if they ever think to pause from survival mode, they can see the hills, the mansions, the gleaming skyscrapers beyond reach, the towering campaniles of universities where they can never afford to send their children.

This place is characterized by the crowding of impoverished human beings, most of them of African and Latin American descent, into hollowed out industrial zones where factory buildings and abandoned warehouses echo the bustle of past decades. This economy of yesterday was exported to the new shop floors of China. Among the only things left are the toxic plumes of chemicals spreading slowly under fence lines. In this place entire generations face severe poverty and a decimated public sector – especially the schools. Tens of thousands of adults exist, persist, somehow without meaningful work or income. Tens of thousands of house-less persons —likely no longer even part of the statistical surveys used to calculate joblessness and income— wander the streets and sleep in the cracks of weathered concrete each night. Every few months the police slay a youngster under questionable circumstances. Crime is rampant. Violent crime is hard to avoid, part of the overall suffering.

The splendid heights and stratospheric wealth would not be so contemptible was it not hanging directly over such desperate poverty. Of course the two things are not unrelated.

Welcome to the San Francisco Bay Area, in the Golden State of California.

The West Coast financial center of the United States.

The epicenter of the tech industry.

The global vortex of venture capital.

One of the most brutally unequal places in America, indeed the world.

If measured by the same metrics that are used to gauge income inequality within nation states, the Bay Area’s internal divide between its rich and its poor would place San Francisco between China and the Dominican Republic, making it roughly the 30th most unequal state in the world. China is now the estimated home to 317 billionaires. California counts perhaps 90 billionaires. Half of these, mostly white men, live in San Francisco and Silicon Valley. The Census counted 4.2 million persons slipping below their definition of poverty last year in California.

In the distribution of income and wealth, California more resembles the neocolonial territories of rapacious resource extraction and maquiladora capitalism than it does Western Europe. Oakland is more El Salvador than it is EU. The Bay Area metropolis is more Bangladesh than Belgium.

California is just one of seven states that has the distinction of ranking higher than the national average on three basic metrics of income inequality, as measured by the Bureau of the Census. Its gini coefficient of income inequality was most recently measured at 0.47.

The ratio of income between the top 10 percent and the bottom ten percent, as well as the ratio of income between the top five percent and the bottom twenty percent show staggering divides in economic power that few other places in America, indeed the world, surpass.

Source: Weinberg, Daniel H., “U.S. Neighborhood Income Inequality in the 2005-2009 Period,” American Community Survey Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, October, 2011.

The only states that compare to California’s harsh inequalities are deep southern states structured by centuries of racist fortune building by pseudo-aristocratic ruling classes, and the East Coast capitals of the financial sector.

Source: Weinberg, Daniel H., “U.S. Neighborhood Income Inequality in the 2005-2009 Period,” American Community Survey Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, October, 2011.

The economies of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama remain bound by racial inequalities founded in slavery and plantation agriculture; the wealthy elite of all three states remain a handful of white families who control the largest holdings of fertile land, and own the extractive mineral and timber industries, and the regional banks.

Texas, with its sprawling cities, global banks, energy corporations, universities, and tech companies, is more like California in that its extreme economic inequalities are as new as they are old. Stolen land and racial segregation combine with unworldly new fortunes built on the Internet and logistical revolutions in manufacturing and markets to manifest a gaping divide in power and wealth between the few and the many. The Texas border, like California’s, opens up vast pools of Mexican and immigrant labor for super-exploitation by agribusiness and industry.

The same goes for New York, Connecticut, and Washington D.C. the other most unequal places in the United States. New York and Connecticut, like California, have become societies divided by an upper stratum of financial-sector workers and corporate employees whose salaries and investments simply dwarf the bottom half of the population’s earnings, and unlike the South, this extreme level of inequality is rather new in its source of valorization. Washington D.C. is split between the federal haves, mostly fattened contractors who run the military, or who represent the interests of the billionaires in California and New York, and the have-nots, mostly Black and immigrant service sector workers who wait on these technocrats of empire.

It’s a strange club, the super-inequitable states of the U.S. This exclusive list pairs the bluest coastal enclaves of liberal power with the reddest Southern conservative states. In terms of wages and wealth these places have a lot in common.

San Francisco’s real estate roller coaster. The Financial Crisis cut 20% off home values in San Francisco, but the U.S. Federal Reserve’s bond buying program, coupled with broader tax and fiscal policies, has created a rally in securities markets, handing the wealthiest Americans enormous gains in net worth. These economic policies benefiting the rich are evident in San Francisco’s real estate prices. Secondarily is the Tech 2.0 boom in San Francisco and Silicon Valley, pulling in thousands of new residents to work in Internet, biotech, and other industries where six figure salaries are the norm.

In San Francisco homes now routinely sell for millions. Not mansions. Not even particularly large houses. Just simple homes built decades ago. In most other markets they would fetch the national median home price of about $170,000. San Francisco, which locals like to call “the City,” sees dozens of real estate deals every month in which a cool million or two pass hands, and afterward the new owner, usually someone with freshly minted tech or finance money, has the modest structure demolished and scraped away. The new thing is to build upward, and lavishly, from scratch. Heated stone bathroom floors and wine cellars are popular. Securing a pad in Noe Valley or Bernal Heights for a few million is seen as a reasonable way to spend money.

In San Francisco the western end of Broadway is known as “billionaire’s row.” Quite a few of the side streets and parallel avenues like Jackson, Pacific, and Washington are lined with estates that trade hands on occasion for a few tens of millions. No tear downs here. The villas and manors along these avenues were built by sugar barons and banking tycoons of centuries past. Silicon Valley’s most senior executives, and the City’s hedge fund managers, buyout barons, bankers, and a few celebrities make up most of the neighborhood’s owners. Their children attend exclusive private schools in Pacific Heights where they are preened for Stanford and Princeton.

It is becoming hard to identify any part of San Francisco as an “elite” enclave. Tech 2.0, as the Google and Facebook-led regional boom is being called now, has vested thousands of twenty somethings as well as senior executives with billions in IPO cash and billions more in salaries to hunt for real estate, and they have chosen San Francisco, nearly all of it, as their preferred stomping grounds. Maybe it will only be another decade until Broadway starts getting called trillionaire’s row.

Sea View Avenue, Piedmont, California. 71 percent white, only 5 percent of Piedmont’s population is Black or Latino. Median household income is $200,000, and wealth holdings are much more. Piedmont supports its own public schools, police force, parks, and libraries.

Across the Bay is a slightly more modest version of billionaire’s row, probably better called a millionaire’s row running across the ridge line from Oakland north to Kensington. In the middle of Oakland, in fact completely surrounded by the scrappy industrial city by the Bay, is the city of Piedmont. When it was founded in the 1920s its first residents gave it the nickname “city of millionaires.” They restricted housing to single family residential homes on large lots from the start to prevent Black and immigrant families from moving up the hillside. Sea View Avenue is where the big money that wants to show off buys real estate, but the entire city boast a median home price of $1.4 million. The Berkeley hills are similarly rich and populated by an unusually high number of lawyers.

Lawyers, especially tort defense, corporate, and tax lawyers who serve the wealthy and defend corporate America from labor unions, environmentalist, and consumer advocates, also love Marin County. Across the Golden Gate from San Francisco, Marin is not much more than a bedroom community for corporate lawyers and CEOs who want a little more room and sun than San Francisco provides. If Piedmont was a city shelter to exclude the working class, then Marin is similar, but on the level of a county. Despite growing pockets of Latino poverty in older towns like Novato and San Rafael, Marin remains one of the wealthiest counties in the U.S. on a per capita basis. Marin’s Black population is segregated into the tiny Marin City, one of the only places public housing was allowed to be built. Marin City’s residents work in the retail sector and some of the industry along San Rafael’s waterfront. They earn near the bottom of the region’s wage scale and subsist on a fraction of the income their wealthy neighbors take in each month.

Hagenberger Road, East Oakland. Oakland is over 50 percent Black and Latino. Sections of the city such as the area pictured above are 90 percent non-white. In the typical pattern of environmental racism, residential homes are in close proximity to major roadways, highways, rail lines, industrial facilities, scrap yards, and utilities.

Unemployment stalks the working poor of the Bay Area, threatening to force them into insolvency and bankruptcy, foreclosure and displacement. During the first Dot Com boom of the late 1990s unemployment was at five percent for white Bay Area residents. For those living along the billionaire’s and millionaire’s rows, unemployment is a meaningless concept. The capital invested by the rich, by their clever advisers who run the hedge funds and private equity shops, earns interests and returns on equity far larger than any years honest wage labor can eek out. The tax code provides for this with carried interest and the lowest personal income tax rates for top earners in many decades. Hordes of tax lawyers, many who live in Marin, the Oakland hills, and San Francisco, will eagerly structure a family’s investments and bills to minimize taxes, so long as they possess a minimum of $5 million in liquid assets – preferably more.

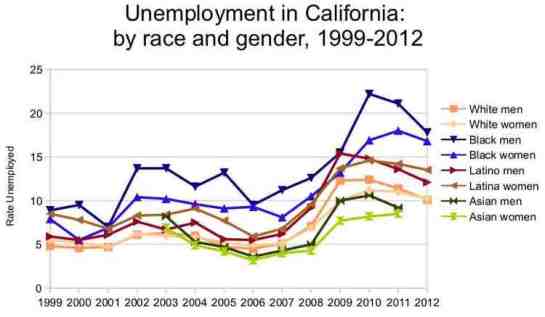

Black men in the Bay Area have consistently suffered an unemployment rate double that of white men. Through the entire George W. Bush presidency, a period characterized by an economic policy to benefit the wealthiest with low taxes and interest rates, Black men endured double digit unemployment rates, reaching about 13 percent when Obama took office. The Financial Crisis sent Black unemployment rates skyrocketing in San Francisco, Oakland, Richmond, and Vallejo, upwards of 22 percent in 2010.

Economic policies under Obama —both those he championed, and those he compromised on— have been very good for the wealthy, and that’s reflected best by the real estate and consumption bubbles frothing over places like San Francisco. The Federal Reserve Bank’s unprecedented purchases of bonds and its low lending rates have produced rallies in stock and debt markets which have greatly re-inflated the fortunes of the rich.

Economic policies under Obama —both those he championed, and those he compromised on— have been very good for the wealthy, and that’s reflected best by the real estate and consumption bubbles frothing over places like San Francisco. The Federal Reserve Bank’s unprecedented purchases of bonds and its low lending rates have produced rallies in stock and debt markets which have greatly re-inflated the fortunes of the rich.

The Pew Research Center recently summed up this polarizing redistribution of wealth from the bottom to the top by noting simply that since 2009 the wealthiest 7 percent of Americans experienced an increase of 28% in their net worth, while the bottom 93 percent actually lost 4 percent of their savings.

The Pew Research Center recently summed up this polarizing redistribution of wealth from the bottom to the top by noting simply that since 2009 the wealthiest 7 percent of Americans experienced an increase of 28% in their net worth, while the bottom 93 percent actually lost 4 percent of their savings.

The San Francisco Bay Area’s current tech boom is further dividing the wealthy few from the impoverished masses. Companies like Google, Apple, and Oracle are among the least diverse workplaces places where men outnumber women, and white and Asian employees dominate the ranks of lowly programmers and senior executives. The need to hire thousands of engineers is drawing waves of college graduates to Silicon Valley and San Francisco, and they’re washing over the current residents like a tide of suffocating oil. Some of the tech buses —private transit systems operated by Silicon Valley’s largest firms to shuttle employees from San Francisco to their suburban campuses in Santa Clara County— now run lines into Oakland and Hayward, a sign that their employees are increasingly colonizing formerly undesirable zones of real estate.

The drift apart between the pale wealthy few and the impoverished multitudes of darker-skinned peoples is evident on the level of whole cities. San Francisco enjoys robust public finances, high credit ratings, low per capita debt to income ratios, and many well funded public services. However, two decades of intense gentrification mean that this healthy public sector increasingly caters only to those “citizens” who can afford to live in San Francisco.

Pushed out of the region’s urban core, in the 1990s and 2000s Black, Latino, and some Asian immigrants found themselves in the affordable locales of Vallejo, Stockton, Richmond and Oakland. Further out towns like Antioch, Brentwood, and Pittsburg became increasingly non-white and working class. In the Financial Crisis these cities hemorrhaged residents and revenues due to some of the highest foreclosure rates in the nation. Vallejo and Stockton went bankrupt after slashing the most basic services. Vallejo is 75 percent non-white. Stockton is 80 percent non-white.

The wealthiest Bay Area communities, the “towns” of Hillsborough, Woodside, Atherton, Los Altos Hills, and the city of Piedmont are three quarters white with median incomes in the six figures. Public finances barely flinched during the Great Recession. A few of these local governments in fact have no outstanding public debt.

Atherton and Los Altos Hills have zero bonded public debt.

Oakland has almost a billion just in bonded debt.

In the tony Marin hamlet of Fairfax the public debt burden resting on each resident is about 1.7 percent of their annual income.

In Richmond the ratio of public debt to personal income for each resident is 16 percent.

Richmond, a quarter Black and a third Latino, is a tangle of oil and chemical refineries run primarily by Chevron. Not a year ago a massive fire at one of the company’s plants spewed toxic vapors and smoke into the sky, poisoning thousands of residents.

Chevron is headquartered in San Ramon, another exclusive, mostly white suburban environment with low municipal debt and a household median income of $121,000 a year.