In a recent profile story for the East Bay Express my colleagues Ali Winston, Elly Schmidt-Hopper, and I noted that Oakland mayoral candidate Bryan Parker doesn’t support a minimum wage measure that’s picking up lots of signatures, and which will likely be on the city’s ballot this fall. The measure would require all employers in the city of Oakland to pay their workers at least $12.25 per hour.

When we asked Parker about the minimum wage measure in an interview we weren’t surprised by his non-supportive answer. Parker is a business executive who ran a division of DaVita, a Fortune 500 healthcare company that pays many of its workers very low wages. Previously Parker worked at several investment banks, the sorts of places where conservative, anti-labor economic opinions are dominant.

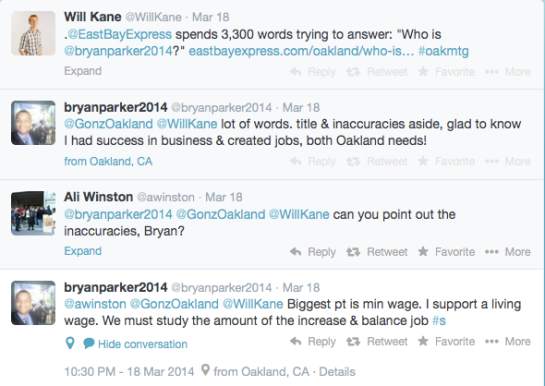

But a few days ago on Twitter Parker claimed we misunderstood and mischaracterized his position on wages. He tweeted that he supports a “living wage.”

To clear up the record, here’s what Parker actually told us. We asked him, “do you support a $12.25 an hour minimum wage such as the ballot measure that will likely be put to voters?”

To clear up the record, here’s what Parker actually told us. We asked him, “do you support a $12.25 an hour minimum wage such as the ballot measure that will likely be put to voters?”

Parker didn’t respond with a “yes.” Parker told us that he supports the idea of a “living wage,” but that he isn’t sure “what the right number is.”

He then said something rather dismissive of the entire idea of using government to raise wages for the working poor. “What I want to think about instead [of a minimum wage] is more full employment,” concluded Parker.

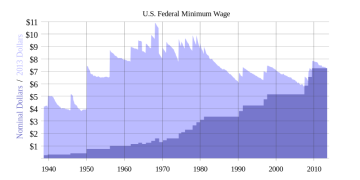

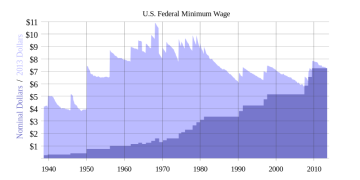

The real value of the federal minimum wage has been made to decline since about 1968. This is one of the major causes of rising household income inequality in America. Ronald Reagan’s term in office coincided with the most consistent and effective attack on the minimum wage.

That’s supply-side economics at its most pure, and it’s also a talking point that has been used by opponents of minimum wages for decades. So to be really clear, when we asked about a minimum wage, we got an answer that wasn’t supportive, and that instead pointed towards a “rising tide lifts all boats” sort of plan.

Here’s the reason we likened Parker’s economic thinking to Ronald Reagan (see 1:33 mins in).

To be fair to Parker there’s some theoretical logic behind the full employment goal. In labor markets with lower unemployment rates companies have a harder time recruiting workers, even for the most unskilled of jobs. Tighter labor markets lead to rising wages as employers scramble to hire employees and retain them. Workers don’t fear quitting or losing jobs as they can just take another one. Wages tend to rise slightly during periods of low unemployment as workers have a smidgen of bargaining power.

Parker also told us he’s cautious about minimum wages because he believes they actually cause unemployment. “Employment would decrease,” said Parker. “Employers wont be able to afford as many employees. There’s extensive studies by economist showing that every time a minimum wage has been raised there’s been a deflationary impact on the overall jobs market.”

Again, that’s a very Reaganesque sort of statement. (See the above video link.)

Switching back into his business executive mode, Parker then told us that he’s a “data driven person.” This is why he doesn’t support a minimum wage and instead offers up the goal of growing jobs.

Problem is, a lot of the economic studies that claim to show a causal link between rising minimum wages and job losses are conducted by researchers working directly for pro-business, corporate-funded think tanks. When your paycheck comes from business interests who will profit from driving down wages, is it any surprise your findings are that higher wages for the lowest-paid workers are bad for the economy, even bad for those very workers?

For a recent example of this logic see Mark Wilson’s “The Negative Effects of Minimum Wage Laws.” Wilson’s consulting firm Applied Economic Strategies, LLC writes economic propaganda for the wealthy elite, attacking higher wages for workers, arguing that unions are obsolete, promoting tax cuts for the wealthy, among other policies that redistribute income and wealthy upward. Wilson was once employed by the Heritage Foundation, a think tank funded by ultra-conservatives like the Koch brothers and he served in George W. Bush’s administration. Oaklanders can probably expect some studies along these lines to be offered up this election season by local opponents of the minimum wage campaign.

The actual academic, peer-reviewed studies on the minimum wage don’t support Parker’s “data driven” opinions. Whether a higher minimum wage causes unemployment to rise at the bottom of the labor market is a controversial question that has been debated since Congress passed the first minimum wage law in the aftermath of the Great Depression, 1938. (It’s been debated alongside child labor laws — those opposing restrictions on using kids as workers in mines and factories were the same people opposed to mandated minimum wages.)

In fact, some studies show minimum wage increases actually bumped up employment rates.

Other state-level studies have shown that minimum wage hikes have led to job losses for low wage workers, but that the overall impact was still to redistribute hundreds of millions of dollars in income downward, even after accounting for lost income from fewer jobs, thereby improving the economic conditions of low-wage households.

A reason for the contradictory results, however, is that the minimum wage is an obviously political issue. It’s at the center of a power struggle between workers and businesses over the distribution of income from economic activity. Enacting minimum wage laws, or raising them on a statewide levels, or even in large metropolitan areas, causes the direct redistribution of millions in income from the top earners to the lowest paid workers. The net effect is probably to redistribute income from wealthy and middle class households to the poor, thereby lifting up the workers with the greatest needs. Many researchers who attempt to gauge the impact of the minimum wage on employment levels are already out to prove either the good or the bad in the policy. When researchers pick their methodological tools, data sets, and statistical formulas, it’s often the case that they’ve already subtly biased the outcome. The kinds of studies you trot out in support of your argument are just that; ammunition to support whether or not you’re for redistributing aggregate income downward via the minimum wage.

But overall the research —not just economic studies, also sociology, history, and not least the actual experiences of working poor families— is pretty clear. Minimum wages increase the overall share of income claimed by the bottom quartile or so of the workforce.