A 2000s housing development adjacent to Stockton’s debt-financed new marina. Stockton over-extended itself by borrowing from banks, the state, and other creditors in the 2000s.

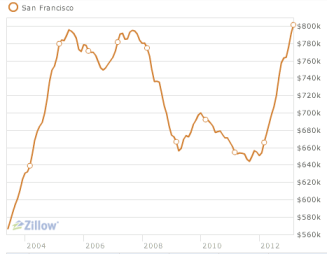

In 2007 the city of Stockton, California was riding the nation’s housing boom. Property tax revenues had more than doubled over the previous seven years, and sales tax receipts were up by 65 percent. Two hours by highway from San Francisco, Stockton’s leaders did not want to become just another bedroom community for commuters, and they rejected their past as a sleepy agricultural town. Flush with cash and an influx of tens of thousands of new residents seeking the more affordable housing going up on the city’s periphery, Stockton’s politicians attempted to remake their city into a destination.

Mimicking the borrowing binge in credit markets of housing developers and home buyers, Stockton’s government issued several major series of bonds to finance what was the most ambitious downtown redevelopment scheme in recent California history. Seven bond issues in the 2000s put Stockton deep in debt to build a downtown arena, a minor league ballpark, a marina, to purchase an eight-story office building to serve as the new city hall, and to build a massive parking garage nearby. And Stockton added to this debt with a pension obligation bond issue that was intended to forward fund the city’s retirement system with $124 million, and to free up cash for other projects.

When the economy crashed in 2008, Stockton became the basement floor to which other distressed California municipalities could look and say, ‘at least we’re not down there.’ Stockton’s lawyers frankly described the crisis in their bankruptcy memo:

“The Great Recession hit Stockton hard. Housing prices plunged, causing property tax revenues to fall, and unemployment has soared during the last five years, resulting in a decline in sales tax revenues. Meanwhile, the City’s expenses have remained the same or increased. Poor decisions, lax management, and bad luck have exacerbated the City’s financial woes.”

As Stockton’s revenues dried up, the city’s financial managers slashed virtually every service and program, including basic vital services. At first the cut to the bare minimum. Then they cut far past levels considered minimal and necessary to keep the city safe and functioning. Stockton depleted its meager reserve funds, transferred funds internally between accounts, and then extracted cuts from its workforce. Labor contracts were renegotiated, and when the city’s two largest unions refused further pay cuts, Stockton unilaterally reduced their compensation by $12.5 million. Employees were unilaterally forced to take furloughs, and then the layoffs began. Between 2008 and 2012 Stockton let go 472 employees, 25 percent of its workforce. Still deficits continued. The city shuttered a fire station. All of this happened just when Stockton needed more resources than ever to deal with a record rate of foreclosures surpassing most other cities. Still revenues declined. In 2011 and 2012 Stockton entirely canceled repair and replacement projects meant to keep city infrastructure and vehicles in working order. The city was allowed to crumble.

All through the carnage of one of the largest municipal financial disasters in American history Stockton continued to make payments on its debt. But in March of 2012, after forcing city workers and residents to shoulder spending reductions, the city finally defaulted on $2 million in bond payments. Three months later Stockton filed a petition for bankruptcy.

Stockton’s bankruptcy process, boiled down to its essentials, is an effort to impose a shared pain among the city’s creditors who are owed hundreds of millions. Some of Stockton’s creditors are contractors that are owed pay for construction projects, or goods and services already provided. Others are workers owed pay and benefits for labor already provided. The other big category of creditors includes financial investors who loaned Stockton capital during the 2000s boom.

Although many of Stockton’s financial lenders gave the municipality money understanding fully that their deal with the city was a speculative investment that carried risks, they now are arguing that the compensation owed to current and former city employees should be cut in order to increase the value of their debt claims on the Stockton. In other words, the financial lenders are arguing that the risk they assumed when they bought Stockton’s bonds should be retroactively transferred to the city’s employees in the form of cuts to their pensions.

Franklin Advisors, Inc., part of the Franklin Resources group, better known as Franklin Templeton Investments, a San Mateo-based financial company that controls about $900 billion in assets, has been most aggressive in pushing this argument. Lawyers representing Franklin Advisers are arguing that U.S. federal bankruptcy laws trump California’s law that says pensions administered by CalPERS cannot be reduced through municipal bankruptcy. If they win, Franklin Advisers will reduce their losses by forcing CalPERS, the administrator of many of the city’s retired workers’ pensions, to pay the costs of some of their losses. This cost ultimately falls on the 1.6 million public employees who collect, or someday will collect a CalPERS pension.

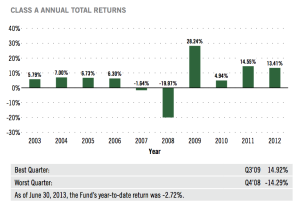

Annual total returns for investors in Franklin Advisers’ California High Yield Mutual Fund. (Source: Franklin Municipal Securities Trust Prospectus, October 1, 2013.)

Franklin Advisers manages several mutual funds which purchased Stockton’s bonds as speculative investments. If you read the bond prospectuses Stockton provided to investors like Franklin Advisers, there’s extensive disclosure of the various risks including potential default on interest payments and even loss of principal. For example, the disclosure statements for Stockton’s 2007 Pension Obligation Bonds included six pages warning investors about various risk factors that could reduce returns or even wipe out their investment. Redevelopment bonds issued by Stockton in 2006 included the warning that a drop in city revenues could lead to losses for investors. All of Stockton’s borrowing from the capital markets came with these boilerplate warnings.

Furthermore, if you read through the prospectuses that Franklin Advisers provides for investors in its mutual funds, the riskiness of investing in municipal bonds of the quality they aimed for is obvious. “You could lose money by investing in the Fund,” explains Franklin Advisers to its clients. “An issuer of debt securities [like Stockton] may fail to make interest payments and repay principal when due, in whole or in part. Changes in an issuer’s financial strength or in a security’s credit rating may affect a security’s value.” It really couldn’t be clearer than that. Well, maybe it can. Franklin Adviser’s California High Yield Municipal Fund also warns investors that:

“Because the Fund invests predominantly in California municipal securities, events in California are likely to affect the Fund’s investments and its performance. These events may include economic or political policy changes, tax base erosion, state constitutional limits on tax increases, budget deficits and other financial difficulties, and changes in the credit ratings assigned to municipal issuers of California.”

Even so, Franklin Advisers is hoping to recoup some losses that it knew were possible when it purchased Stockton’s bonds.

If Franklin Advisers succeeds, who specifically will benefit? First of all, Franklin Resources benefits, as do financial companies like it. If it can establish the precedent that municipalities must cut pensions in order to pay back bondholders, then the value of many of the bonds of distressed municipalities owned by Franklin will increase in value.

So who is Franklin Templeton?

Gregory E. Johnson, grandson of the founder of Franklin Resources, Inc., currently the company’s Chairman and CEO, and owner of $4.9 million shares of Franklin Resources worth $336 million.

The real force behind Franklin Resources is the Johnson family, a clan of billionaires who inherited their wealth from Rupert Johnson, Sr., the company’s founder. In 1973 Rupert Sr. moved Frankling Resources from Wall Street to San Mateo, California. The company grew over the next four decades to become one of the largest institutional managers in the world. And Franklin Resources’ ownership remained rather closely held. Although it has 631 million shares of outstanding stock, members of the Johnson family still control close to 230 million shares, 36 percent.

The Johnsons are billionaires. Rupert Johnson, Jr., and Charles B. Johnson (who I’ve mentioned before on this blog), brothers, both own over 100 million shares in their father’s company. Charles B’s children, Charles E. Johnson, Gregory Johnson, and Jennifer Johnson all own slices of the company.

Ironically CalPERS itself owns over 467,000 shares of Franklin Resources, worth about $63 million. But that’s a mere 0.1% of Franklin Resources total market capitalization, and an even more insignificant sum, two hundredths of one percent, of CalPERS total assets under management. So CalPERS and its retirees gain nothing from their little stake in Franklin.

The investors in Franklin Resources who would benefit from a win in court against CalPERS and Stockton would include the wealthy individuals who own shares in Franklin’s municipal bond mutual funds. Municipal bonds have always been a preferred investment of wealthy households because of their federal tax exemption. Wealthy California investors have the added incentive to buy into funds like Franklin Advisers’ California High Yield Municipal Fund because income from it (which flows from the interest payments that Stockton and other cities pay) is exempt from California’s relatively high state income tax. The after tax value of tax-exempt municipal securities to wealthy individuals and couples in the top federal and state tax brackets is often more than double the value of what’s available in the corporate bond market, and the risk of default is generally less. Now it would seem Franklin hopes to reduce that risk to its wealthy clients even further.